Rachna Agarwal sees designing seaside homes as an art. It is an invigorating challenge to find the right balance between materials, design, and climate/weather requirements. The Delhi-based architect realised this five years ago, when a client asked her to redesign a sea-facing house in Goa; the client ended up buying the Portuguese-era bungalow in North Goa.

Architects and designers share that, over the last decade, the approach to construction of sea-facing houses has changed. As more people leave crowded metros to find peace in coastal towns, houses are morphing from vacation spots that lie vacant for the majority of the year to inviting spaces for families to reside in, at least for a few months at a stretch. Advances in technology and the quality of materials available in the market are also helping this boom. Many of the architects we spoke to recall clients coming to them with well-researched concepts of what they want.

The Cove, a 5,000 sq ft beach house in North Goa, designed by Rachna Agarwal

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Heat, moisture and strong winds are defining climatic conditions of coastal regions. They hasten corrosion, and seepage and leakage are ever-present concerns — all of which can shorten the life of a structure. Nowadays, many architects prefer wood or aluminium for construction as both are durable and sustainable options on the coast. Agarwal, the co-founder of Studio IAAD, says, “In Goa, we normally prefer aluminium over wood because it is long-lasting and requires low maintenance. After a few years, some types of wood develop cracks which are not suitable for homes that are closer to the sea.” At Cove, a 5,000 sq ft beachside house in North Goa, she designed the facade with textured tiles and concrete, as the texture discourages moss growth and no maintenance is required. The house has a sloping roof that tilts on its axis — the tilt helps tackle torrential rains while also letting the sea breeze in.

The Cove’s textured tiles and concrete facade

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Natasha Kochhar, an associate partner of LTDF Architecture in Delhi, asks her clients how they plan to use the house that they are buying. Her design changes depending on whether they will stay there permanently or use it as a vacation hideaway. Her definition of permanent: 150 days. “If anybody is using a house for more than 150 days, I prefer using aluminium for the cladding [which is durable and rust-proof]. I also ask them about the location of the property. Even if it isn’t facing the sea, but is in a seaside town, my first preference is aluminium.”

Vote for hardwood

But there are advocates for wood, too. P.L. Narayana, the founder of NESCA Homes in Hyderabad, advocates for wood as the major constructing material. “In the past five to eight years, several architects have been using wood not only to construct bungalows and villas, but also for multi-storey buildings. And wood [especially from managed forestry] is a sustainable material.”

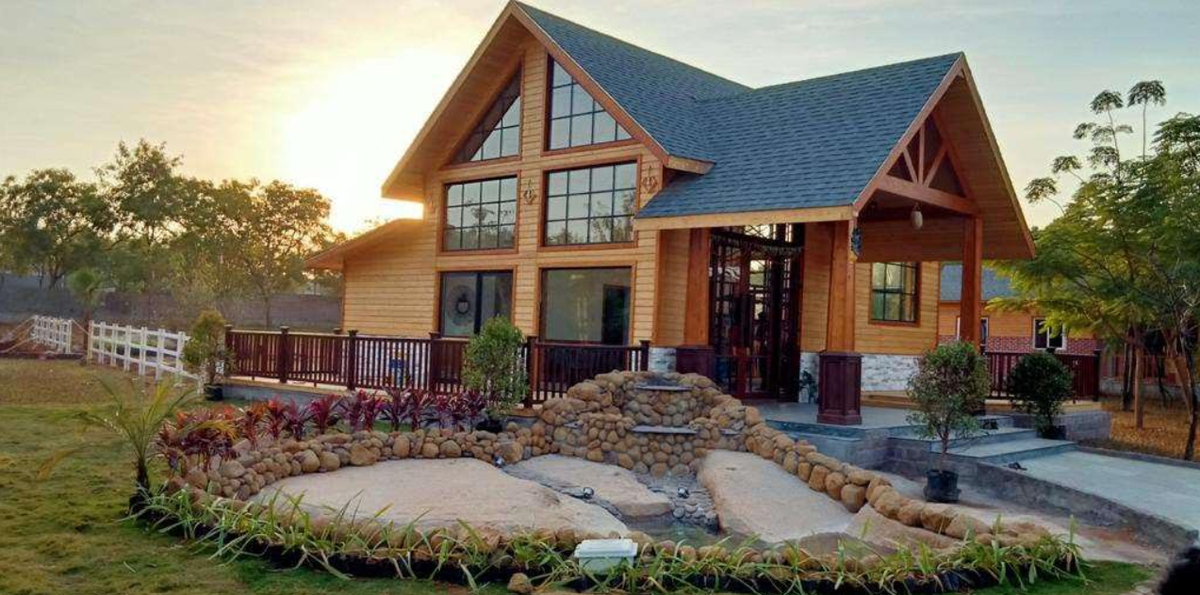

One of NESCA Homes’ wood houses

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Though aluminium is easily available and is definitely better when compared to other metals like iron in terms of corrosion for seaside structures and its lightness, he believes that wood is a better thermal insulator. “It has the best sound absorption and is also warmer, which helps 60% savings on heating and air conditioning per year. And it betters your carbon footprint because it absorbs carbon dioxide,” says Narayana, who is currently working with ITC for a commercial project in Port Blair, building 50 sea-facing residences.

Hardwoods are resistant to water and weathering, and do not scratch or splinter easily. (Besides local varieties like ain — which architect Bijoy Jain used to great effect in his stunning Palmyra House in Alibag — India also imports Douglas fir, yellow cedar, spruce, pine and the like.) The fact that a wooden building is lighter than a concrete one also means the gravitational load is reduced, thus taking away the need for large amounts of concrete in the ground for the foundation.

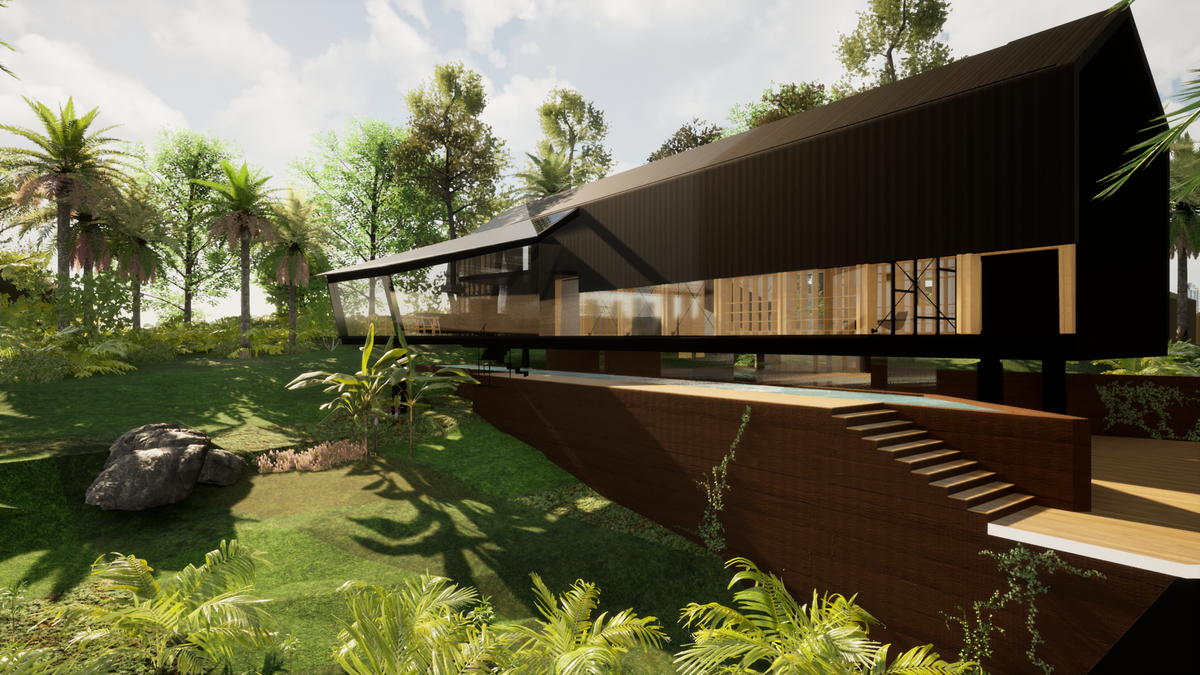

Akshat Bhatt, the founder of Delhi-based Architecture Discipline, recently designed a residence made entirely out of mass timber in Goa. He used new-age materials such as architectural fabric and thermally-treated cork to push the sustainability factor. “The project generates its own power, it is advanced in the way waste is treated on-site, and it only uses naturally-ventilated air because it is good for humid environments,” he adds.

Akshat Bhatt’s mass timber house under construction in Goa

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Metal for the win

Further down South, Sunil Philip, director at PSP Design in Chennai, chooses Corten Steel — with its rusty appearance that amps up its aesthetic qualities — for seaside construction. “It is ideal because the material rusts, which acts as a protective layer,” he says. It is also anti-corrosive and low maintenance.

On the other hand, Biju Kuriakose, the co-founder of architectureRED in Chennai, prefers a mixture of materials, from high-end aluminium, stones or bricks, and anything that is available naturally.

Clockwise from top left: Biju Kuriakose, Rachna Agarwal, Natasha Kochhar, P.L. Narayana, and Akshat Bhatt

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Tackling corrosion

In the last few years, architects are increasingly gravitating towards eco-friendly, energy-efficient and sustainable building materials, which are also corrosion-free. “Some of the important materials to consider while developing a seaside project are Corrosion Resistance Steel [CRS] TMT bars, ground granulated blast-furnace slag [that has a slower rate of hydration which helps in reducing the permeability of concrete], and Cera Cote Protecto series [which creates a high water barrier effect],” says Ram Raheja, managing director of S. Raheja Realty in Mumbai.

He also points out that special attention must be paid while choosing hardware and joints because they can corrode quickly thanks to slant rain and salt spray. Using weatherproof flooring materials and keeping a sharp eye out for leaks or rust are important, too.

A rendering of Bhatt’s mass timber house in Goa

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

With sustainability in mind

Wood scores high on the sustainability and eco-friendly scale. “Trees can re-grow in 10 years, whereas metals take centuries to re-form,” says Narayana. “Moreover, wood is a whopping 1,770 times more energy efficient than aluminium.” Kuriakose agrees. “Wood brings warmth to a house. If there is no wood, then it will be too cold inside an apartment or house.” But he adds a caveat: wood will require periodic maintenance.

According to Philip, another important factor is ventilation and the minimum usage of electrical products such as air conditioners. “There should be enough space for air to pass. Proper cross ventilation will help avoid the usage of too many electrical products,” he says.

A beachfront property

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

In most of her projects, Agarwal encourages clients to plant saplings or trees. “In Goa, any kind of plantation will look beautiful. We suggest banana trees, bird of paradise or spider leaves.” This will also help increase the green cover in the area. She also recommends, if the budget permits, “the installation of solar panels, which help in the long term”.

Kochhar addresses ventilation through large windows in the units that she designs “Ideally, I prefer 10×12 windows. But depending on the wind speed and accessibility, they can be altered. For example, if a house is located on a hilltop, then it is difficult to carry window panes.”

First buyer advantage

In smaller cities, like in Goa, or in places like Alibag, many clients are second-time buyers, preferring to invest in seaside homes as a luxury retreat. But in tier 1 cities like Mumbai and Chennai, especially along the East Coast Road, many choose such properties for a better quality of life. In Mumbai, the clients of major realtors are either first-time buyers or choose redevelopment projects. “The scenic view of the seafront in a hustling city like Mumbai is considered to be a utility of its own. And the aid of high-class amenities like terrace gardens, infinity swimming pools, green open spaces, higher ceilings, etc, amplify the architectural impact of such a project.” He adds that realtors are now coming up with modern amenities to attract millennials and first-time buyers.

Keeping rainwater out

Finally, with climate change wreaking havoc across the globe, and rainfall drastically increasing along the Indian coastline, any seaside construction must take necessary precaution against flooding. “The way to tackle the issue is to understand the strengths and opportunities that are presented in the form of open spaces,” explains Raheja.

“The idea is to increase the number of pervious [porous or permeable] surfaces, and encourage designs, policies, collaborative and participatory strategies like buffer zones along the river to include more blue-green infrastructure, rainwater co-management in built areas, and converting open spaces to mitigation greens, which can reduce the load of stormwater management on the main grid.”