Kerala not the worst

Yet, the magnitude of Kerala’s human-elephant conflict — projected as acute enough to trigger even political agitations — is not commensurate with the state’s relative abundance of wild jumbos.

Of the estimated nationwide population of 30,000 wild elephants in 2017, Kerala had about 5,700, or 19%. Between 2018-19 and 2021-22, elephants killed 2,036 people in India, data collected by the central government show. Kerala accounted for only 81 (4%) of these deaths. (Field data add up to 92 deaths.)

Clearly, the conflict in Kerala is not comparable to the situation in, say, North Bengal or Odisha, where smaller jumbo populations are blamed for much bigger human casualties.

But Kerala has seen a relative spike in the conflict in recent years. In 2021-22, the number of human deaths scaled a new high of 35.

Managing perception

Assessment of Kerala’s jumbo conflict depends on who one asks — the tribal populations of the Western Ghats, or the settlers who came there from the central and southern parts of the state.

“Kerala has a history of settler-agriculture since pre-Independence days, and state policy continues to allow such migration. The tribal and the elephant are seldom in conflict, but their ways are alien to the settler who must outcompete both to gain control of the land. Their (settlers’) panic at the so-called conflict is often just optics,” said a sociologist who has worked in the Wayanad hills.

In places like Munnar, conflict tourism has become popular.

“An elephant on the road is neither an imminent threat nor an idle curiosity. All one needs to do is keep calm and allow it space. But people blow horns impatiently and try to drive the animal away. Tourists crowd around, and even approach (the elephant) on foot for selfies. The moment the animal decides it has had enough, it becomes a ‘marauder’ or a ‘terror’ in the media,” veteran wildlife crime investigator Jose Louise said.

Experts underline that simply altering how people perceive elephants can make their interaction a lot safer. However, they agree that on rare occasions, elephants can go rogue, with or without provocation.

Big boys on the loose

As a fraction of all encounters with elephants, the chances of coming across a rogue animal increase with the number of bull elephants roaming outside the forest. That number is on the rise in Kerala.

Elephants have traditionally preferred Kerala’s moisture-rich forests, where they move in from adjoining Tamil Nadu, particularly during the summer months. In recent years, this concentration of wild elephant populations in Kerala has exhibited a significant number of young bulls.

“Over the last two decades, the sex ratio in southern elephant populations, particularly those north of the Palghat gap, has recovered from the onslaught of ivory poachers who ruled these forests and selectively took out tuskers in the 1980s and ’90s,” ecologist Raman Sukumar, who has been working on Asian elephants since the late 1970s, pointed out.

In the matriarchal elephant society, bulls leave the natal herd after the onset of puberty between the ages of 14 and 16 years, and join what are known as boys’ groups to explore new foraging areas under the tutelage of older bulls. Many of them must step out of Kerala’s elephant forests — which are getting increasingly infested by exotic invasive weeds such as Lantana and Senna, leading to a loss of natural forest feed, especially in the swamp areas.

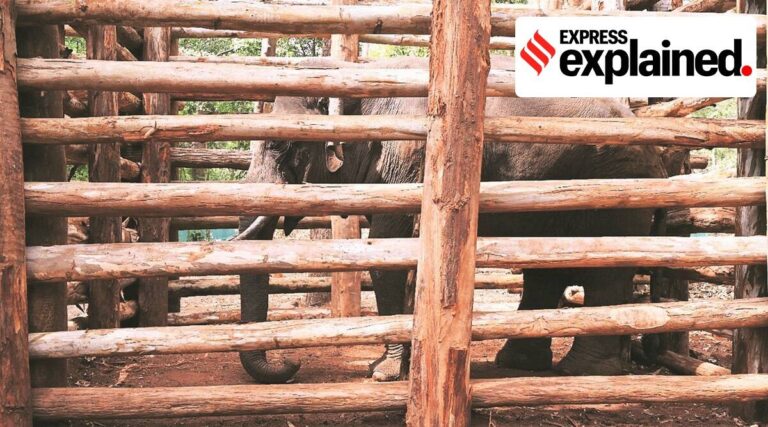

Tackling the rogues

Within the male social order, the training of the young bulls continues as they emerge as mature males after getting musth — a secretion from the head signifying a burst of reproductive hormones for 2-3 months a year — that makes them easily irritable and aggressive, but not necessarily a threat to humans.

However, a bull showing habitual aggression towards people and posing a threat to life and property requires prompt intervention. Provoked by human callousness or not, such rogue behaviour may potentially set the standard for other young bulls to emulate and quickly exacerbate conflict, experts say.

“Welfare of individual animals is a valid concern but not isolating a rogue bull in time puts at risk the future of other bulls in the area. Our experience shows that sparing the brat can spoil the batch,” a retired forest officer said.

Saving a success story

Elephants are far-ranging animals. Most often, fragmentation of habitats and corridors due to legal and illegal changes in land use — clearances for mining, or encroachment for agriculture — squeeze the jumbos and fuel conflict. In Kerala, fortunately, the frontiers between the wilderness and civilisation have remained largely unaltered in recent years.

Changes in agricultural practices in cropland adjoining forests also lure herbivores, including elephants, into conflict. But while elephants do target paddy, banana or tapioca in Kerala’s villages, they have little interest in coffee, pepper or tea — the dominant crops in the plantations.

These factors have contributed to the success of elephant conservation in Kerala and helped limit conflict, otherwise an inevitable cost of such success. Significantly, Kerala recorded only 14 of the 251 elephants (5.6%) that India lost to electrocution and poaching between 2018-19 and 2020-21.

Proactive perception management and stricter enforcement by the state can ease the pressure on jumbos. Also, say experts, a pragmatic policy for problem elephants needs to recognise that zoos and temples are no place for these magnificent animals — and packing them into rescue centres is an untenable drain on resources in the long run. They are best absorbed in forest workforces for patrolling and conflict management.

JUMBOS NAMED FOR THEIR TRAITS

PT-7: Palakkad Tusker-7 (PT-7) was captured after being tranquilised with darts on January 22. He will be tamed and turned into a kumki (captive elephant used for operations against wild elephants). PT-7 was initially named Dhoni after the village where he was first spotted 2 years ago, and which he frequently visited. He liked to feast on jackfruit and harvest-ready paddy; in July 2022, he trampled a man to death.

Arikomban: The elephant got its name, literally ‘rice-tusker’, after it repeatedly raided shops, especially a ration outlet, in Panniyar village in Idukki district to eat rice (ari), atta, and wheat. In a raid last week, Arikomban consumed two sacks of rice. Since it was first spotted in the area five years ago, Arikomban has trampled people to death and destroyed several houses.

Padayappa: Believed to be in his 40s, Padayappa is a wild tusker seen near the hill station of Munnar in Idukki, and in tea estates along the Munnar-Marayoor route. Padayappa raids shops, and although it has not attacked humans yet, it has started to exhibit violent behaviour of late.

Chakka Komban: The favourite food of this tusker (komban) is jackfruit (chakka). He is frequently seen in the high ranges of Idukki, particularly in the Anayirankal reservoir area, and does not have a history of attacking humans.

Kabali: This elephant roaming the Athirapally forest in Thrissur district was named after a Rajinikanth film. Kabali has a tendency to attack or chase vehicles on the Athirapally-Malakkappara forest route. —SHAJU PHILIP