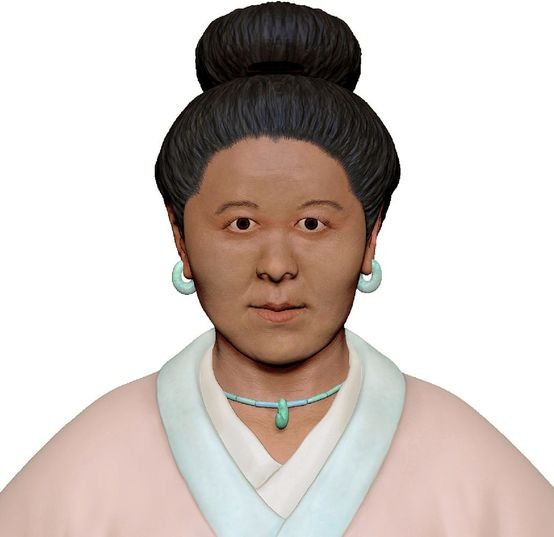

The face and body parts of a woman dating to 1,600 years ago, who was named Himiko of Okitama, are reproduced with computer graphics. (Provided by the education board of Yonezawa city, Yamagata Prefecture)

YONEZAWA, Yamagata Prefecture–A multiple-institute effort using computer graphics and DNA technology reproduced the assumed features of a woman who was likely a person of noble birth 1,600 years ago.

An image and a video of the re-created model released on Nov. 4 show that “Himiko of Okitama” had droopy eyes, a flat nose and black straight hair when she was alive, features that indicate she was a direct ancestor of modern people, researchers said.

Her skin color and hair type were determined based on genetic data from her skeletal remains, which were uncovered in 1982 from the Totsukayama burial mound group in Yonezawa’s Asagawa district.

Seven research institutes, including Tohoku University, worked with Yonezawa city’s education board to reproduce her whole body through such methods as DNA analysis and forensic facial reconstruction.

About 200 graves are located around the foot of Mount Totsukayama in Yonezawa, which is part of the Okitama area.

Himiko’s bones were found in a box-shaped stone coffin in the No. 137 Totsukayama grave, built from the latter half of the fifth century, along with a long-tooth comb and a small knife.

A Dokkyo Medical University study found that she was 143 to 145 centimeters tall. She is estimated to have died at around 40 years old.

The reproduction project started after Tohoku Gakuin University excavated the Haizukayama burial mound site in Kitakata, in neighboring Fukushima Prefecture, in fiscal 2017.

The bones of a man aged 50 or older were unearthed there.

Nuclear DNA was sampled from the ancient woman’s teeth for comparison with the man’s remains. The study found that 96 to 97 percent of her genetic information was well preserved.

“We obtained nearly the entire data of nuclear DNA, or humankind’s design drawing,” said Hideto Tsuji, a professor of Japanese archaeology at Tohoku Gakuin University, who headed the reproduction project. “Such affluent information rarely remains in old human bones.”

In fiscal 2021, Yuka Hatano, an assistant professor of forensic medicine at Tohoku University’s Graduate School of Dentistry, and Toshihiko Suzuki, an associate professor of forensic medicine at the school, started re-examining the woman’s remains and rebuilding her facial features.

The National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo was commissioned to analyze her nuclear DNA.

The right side of the woman’s skull had been lost and the nasal bone was not found.

But the study could show how she likely clenched her teeth, providing a better understanding of her dietary habits and lifestyle.

“Her teeth were found worn down with apparent signs of temporomandibular joint dysfunction,” Hatano said. “The conditions seemingly resulted from her chewing style and other habits, and her jaw was distorted slightly leftward.”

The “drooping eyes” conclusion was based on her skin’s thickness.

The National Museum of Nature and Science’s analysis showed that her hair was straight and black, her skin was brown or blackish brown, and her eyes were a color between black and brown.

She was a descendant of the people who moved from the Chinese continent during the Yayoi Pottery Culture Period (1000 B.C.-A.D. 250).

But some characteristics typical of people from the earlier Jomon Pottery Culture Period (c. 14500 B.C.-1000 B.C.) were also identified in the woman’s remains.

“The Jomon people are said to have had craggier faces and prominent noses, but her nose was flat,” Hatano said. “Relatively large eyes and single-fold eyelids were added to her reproduction.”

Tohoku Gakuin University professor Tsuji said there is a possibility that Himiko and the man in what is now Fukushima Prefecture may have known each other.

“With the advanced radiocarbon (C14) dating technology, an analysis of the human remains from Haizukayama and Totsukayama revealed the two belonged to the same period,” Tsuji said.

“She resembles us, suggesting she is a direct ancestor of us,” he continued. “The research outcome is extremely important, and we wanted to share it with local people through imaging in an easier-to-understand way.”