Black Flag were enjoying an absurdly productive year, releasing three albums (starting with My War) and playing roughly 170 shows. One of these shows was September 25, 1984 at the Mountaineers Hall in Seattle, with a hungry young band called Green River opening. Osbourne, Cobain, and Lukin all went, with Cobain selling his entire record collection to buy tickets. None of them emerged the same. Cobain started spiking his hair, spray-painting cars, and screaming to strengthen his vocal cords. As for Osbourne and Lukin: “The Melvins went from being the fastest band in Seattle to the slowest, almost overnight,” in the words of another Washington punk named Kim Thayil, who would form a band called Soundgarden that same year.

By this time, the Melvins had replaced Dillard with a drummer named Dale Crover, whose mother’s house in Aberdeen made for a makeshift practice space. The fledgling C/Z Records picked them up and put them on a 1986 compilation called Deep Six that was meant to highlight the new sound brewing in the Northwest, but after cutting 1986’s self-titled EP for C/Z and 1987’s Gluey Porch Treatments for Bay Area label Alchemy, Osborne and Crover moved to San Francisco. Lukin alleges that Osborne declined to formally fire him, telling him he’d broken up the band; it wasn’t until Lukin ran into Osborne in San Francisco that he learned the truth. (Lukin would go on to co-found Mudhoney, then retire from music to pursue carpentry.)

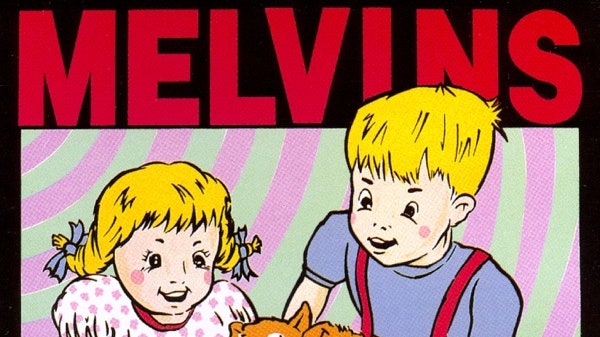

The Melvins’ early years in the city produced some of their best work: Ozma and Bullhead, with Lori Black (the daughter of Shirley Temple, of all people) on bass, and the mighty drone-metal ur-text Lysol, with Joe Preston holding down the low end on an early entry in one of underground metal’s most enviable resumés. Meanwhile their old buddies Cobain and Novoselic were building steam fast in Seattle, exalting the influence of the Melvins at nearly every turn. “You couldn’t buy better advertising,” said Osborne, and soon, major labels intent on snatching up as much of the Seattle sound as they could were looking to this manifestly, militantly bizarre band in hopes they might be the next Nirvana. The Melvins went with Atlantic and booked San Francisco’s Brilliant Studios to make their fifth album, 1993’s Houdini.

If the industry climate was ideal for a band like the Melvins finding an inkling of commercial success, the band’s personal circumstances were not. By the time they started working on Houdini, they’d fired Preston and taken Black back on, but she checked into rehab after being busted for heroin possession in Portland, and Osborne and Crover played bass on most of the album. Meanwhile, ostensible “producer” Cobain was deep into his own heroin addiction and consumed with the making of Nirvana’s In Utero, released on the same day as Houdini. Originally scheduled to workshop songs with Osborne before production, he flew into San Francisco on the first day of sessions and was asleep by 6 p.m. “I went to [Nirvana manager] Danny Goldberg’s office in L.A. and said, ‘Look, Kurt Cobain’s strung out,’” Osborne said. “Kurt was really bad, as bad as he’s ever been.”