“Even in real-time, I felt like throwing up from some of the things I saw. They disgusted me,” says Oren Zeev, not mincing any words. “Of course, I enjoyed the rise in valuations and from the flow of money into my companies, but I wasn’t enjoying myself from an emotional standpoint. I didn’t like the charlatanism. I’d rather be a lot less successful and not have all of this disgusting stuff going on.”

It seems as if Zeev has been waiting a while to release everything he’s been bottling up. This moment has finally arrived after the air has been released from the high-tech bubble and it is no longer necessary to repeat the clichés. “We are now shifting into a mode where only the good will succeed and I prefer that to a situation in which the charlatans also succeed – even if it means I will make less money. Just as in the previous bubble, people didn’t ask how the company will make a profit but only focused on the growth while ignoring the rotten foundations.

“This is the dynamic of a bubble,” noted Zeev. “It develops when you are only looking at the topline, how much a company has grown. This allows you to raise more money and grow further, and so on. Companies grew quickly because they had access to money. Even if they sold something at a loss – whether it was an insurance policy or real estate like WeWork – the consumer didn’t care and sales increased. This inflated valuation further until something went wrong. And then everything was reversed and the bubble burst.

“In the reality of one year ago, anyone who raised a fund registered results that looked good. It didn’t matter what you did, you still made three and four times your investment. You didn’t need to have any competitive advantage or special insight, the tide encompassed everyone.”

You benefited from the bubble.

“Of course I did. But I’ve always tested myself compared to others so when everyone else had returns of four times on their investment, I had 20 times. So now I’m fine when everything is down 50%.”

By nauseating behavior, you mean grandiose billboards? Parties in the Maldives? A private jet?

“How can it be that a company that isn’t profitable has a private jet? (Startup Rapyd reportedly used a private jet). When I know that a company has a private jet and it is still not profitable I know that it will not end well because it means that they are out of touch with reality. My companies didn’t act in such a nauseating way. It isn’t that they weren’t part of the bubble, and some of them got too big too fast, but not in a nauseating manner.”

The crashes are still to come

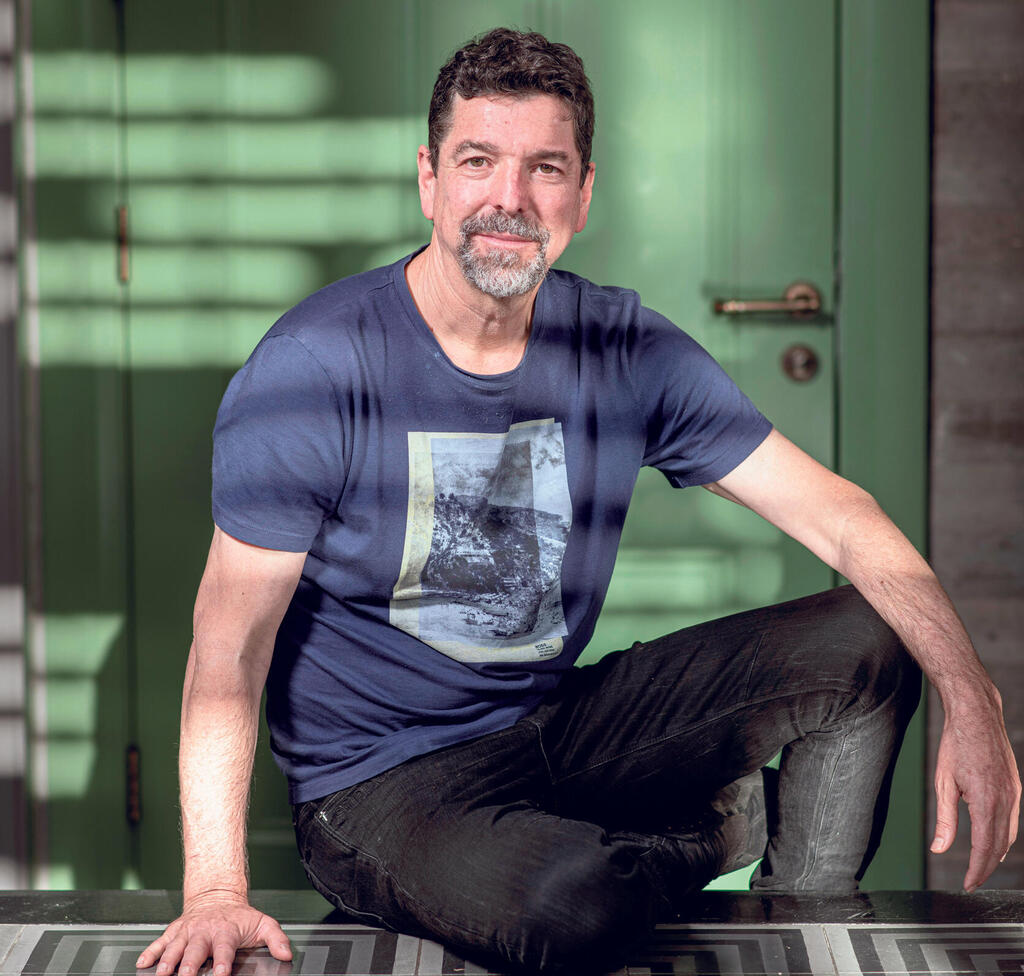

Zeev (58) has been for many years the lone wolf of venture capital investments. He is a rare breed of investor who has no partners, analysts, public relations experts, or even proper offices. His VC, named Zeev Ventures, identifies promising companies at an early stage, invests in them, and nurtures many of them all the way to an exit or unicorn status.

His list of successes includes Audible, an audiobook service in which he invested in 2003 while still at Apex fund and led all the way to a sale to Amazon in 2008 for $310 million. “If this company would have been independent today it would have been worth tens of billions,” he said. “Such a sale after the bursting of a bubble was incredible.”

Another success story is Chegg, an education technology company, of which he acquired 20% in 2008 and led to an IPO in 2013. Chegg is currently traded at a market cap of $3.7 billion after previously peaking at $11 billion.

Over recent years, Zeev was an early investor in several extremely successful unicorns, including TripActions, Hippo, Next Insurance, Houzz, and Tipalti, to name a few.

The crisis in the market has also had a dramatic effect on Zeev’s empire, with Next Insurance laying off 150 of its 900 employees, Firebolt firing 40, Veev sacking 100, and Reali even closing down. Houzz, which was valued at $4 billion and was close to going public, was forced to delay its IPO. The overall value of the unicorns in Zeev’s portfolio has been cut at least in half.

“The sector has come to a grinding halt. That is clear,” Zeev notes. “The drop in valuations is still ongoing. It started with the fall in valuations in public companies at the end of last year, moved to growth stage startups and then to companies lower in the ladder all the way to early stage companies.”

“The main trigger was the sharp increase in interest rates. The market has changed dramatically as far as funding goes. The result of the rising interest rates means that we are now entering a recession and companies are feeling this. They are missing forecasts, cutting investments, and prefer to grow in a more efficient manner, which includes laying off people.”

How much worse will it get?

“We haven’t seen many collapses yet, because companies still have cash. The next stage will arrive when the cash runs out in 2-3 years. We will then discover which companies are doing something which is a ‘must have’ and won’t be hit by the recession and which companies are doing something that is not as necessary. Funds are also having a tougher time raising money now so everything is moving slower.”

Your companies have also dropped in value.

“That’s the way it goes, the situation affects all companies. I’m not saying that every company in which I invested a year ago is valued the same today. Obviously, I have companies that are valued significantly lower. But generally speaking, my companies are very healthy. Even if they are worth less, they are still market leaders and are growing rapidly. They aren’t immune, but they are more successful than their competition.”

“You can divide entrepreneurs by the way they create hype around their companies and by how much they are focused on operations. I’ve never gone with entrepreneurs who know how to create hype and it is no coincidence that I didn’t invest in the likes of WeWork. All of my entrepreneurs are boring. They are responsible, mature, and don’t do coke on a private jet. I don’t have entrepreneurs who know how to sell a story. I prefer the doers over the talkers. In the market that existed over the past decade, the talkers also succeeded. When everything is built around storytelling this nurtures itself. In a normal market, this stuff doesn’t work. Nobody buys it. I’ve been investing for 28 years and I learned how to act in the last bubble. Therefore, generally speaking, my companies are successful even in a period when there is a shortage of money.”

What will be left after this tsunami recedes?

“In the short term you suffer some blows, but the good companies will be stronger at the end of the crisis. Google, Amazon, and Netflix all went through a difficult crisis and barely survived, but ended up exiting it stronger. For example, TripActions suffered a painful blow before everyone else once people stopped flying because of Covid. In 2020 it was forced to lay people off, but this August it was already raising money again at a $9 billion valuation. We knew they would be stronger at the end of this crisis because there is something special about this company, even though the CEO got white hair during the crisis. This is unlike other companies that rose with the tide and have now been caught with their pants down.”

“I remained disciplined and loyal to economic logic. Like, how much does it cost to acquire a client, and how long do they stick around? When it comes to the two most important factors, which are growing and doing it in an economic fashion, I focus on efficiency. I’m willing to forgo some growth for efficiency. WeWork, which is currently worth around $2 billion, a tenth of the money invested in it, is for example a company that grew too fast, and without paying attention to efficiency. My companies do both.”

They are also laying people off like the rest.

“Of course my companies are laying off people. In order to be efficient and stronger at the end of the crisis you have to get rid of all excess weight. Ultimately you can’t be smarter than everyone all of the time. No one can predict the future.”

The efficiency Zeev is referring to is essentially another word for layoffs. Estimates put the number of those laid off in Israeli high-tech over recent months at around 6,000 people, with tech giants of the likes of Amazon and Facebook also firing tens of thousands of employees across the world. “It might not sound pretty, but in my entire history I’ve never met an entrepreneur who told me that they wish they hadn’t fired so many people,” said Zeev.

“Right now it is better just to rip off the bandaid and not do it slowly. People are always surprised by how efficient a company can be with fewer employees. That is why my advice is to do this as quickly and as deeply as possible. Almost every one of my companies went through a difficult period of layoffs. TripActions employed 1,100 people before Covid, fell to 600, and is now at 2,000.”

Elon Musk did this at Twitter, firing thousands of people when he took over.

“There is plenty of justified criticism on how Musk managed these layoffs. It is almost comical and I’m not one of his fans. But should he have laid off half of the people at Twitter? Absolutely. All these monopolies are bloated. Facebook is the same. I’m certain you can lay off another 30,000 people there and nothing would happen.

“It is true that this can be done with more compassion, and at the companies in which I’m involved do so with more compassion. But in the U.S. compassion is behind legal exposure. If there is a theoretical threat to legal exposure they choose the disgusting way.”

You have to date raised over $2 billion in nine funds. Does the crisis reduce your appetite to invest?

“Of course it does. The number of dollars I currently spend each month is significantly lower than it was. The appetite has dropped. But when the right thing comes along it will be back. There will be more opportunities going forward, not less. But this is in the long run.”

Aren’t you afraid to miss the next big thing?

“I don’t get FOMO. I don’t live with the feeling that I’m missing out on something if I don’t do anything for the near future. It is fine to not do anything over the next year. But still, if I see something good I will make a decision immediately. It won’t take me a month to decide. I have money and I’m currently raising a new fund.”

Is it currently more difficult to raise a fund?

“No doubt. But it is a great thing. Because if it is difficult for me that means I will require 10 more meetings before managing to raise the money. On the other hand, other investors will raise a lot less or not at all.”

What will happen to these funds?

“A lot of VCs will disappear. Unlike a company that goes bankrupt, there is no announcement when someone becomes a zombie VC.”

“These are VCs that have a few million and can drive startups crazy but will ultimately only invest $500,000 a year and don’t have the capability to raise a new fund. They continue to take commissions and have a portfolio, but they are irrelevant. Funds don’t die, they just become irrelevant.”

Back to your companies, do you feel that there is any regret regarding what happened over the past couple of years?

“I felt that the market was high, but I felt that also in 2016 and 2018. I don’t believe in my ability to time the market. I have an advantage when it comes to microeconomics, not macroeconomics. Therefore I don’t try to guess when it might be a good time and when it might be a bad time. I want to be in the market at any given moment and find opportunities that I’m excited about. So clearly there will be mishaps here and there. And when the drop comes you look back and see investments that in retrospect were too pricey. Had I known what the valuations would be today I’d obviously not have invested at the previous valuation. In retrospect, I would have made some different decisions, but I don’t look back and think that I was an idiot. I made sure to invest in quality companies.”

Zeev grew up in Haifa and is married to Hagit, a psychologist, and has a son (who lives in the family home in Tel Aviv), and a daughter (who lives in New York). Zeev began his career as an engineer at IBM and in the 1990s entered the investment world at Apex. He immigrated to Palo Alto 20 years ago and has lived there ever since.

In 2008 he began investing his own money, “several tens of millions,” he says, before he raised his first fund in 2015 and began managing the money of others as well. He has insisted on working on his own ever since, not as a default but as an ideology. He rejects every cliché regarding the importance of teamwork. He aims to acquire a significant portion of early-stage companies (20%-40%), and usually maintain his holding throughout subsequent funding rounds.

“I don’t come from a family with money and thanks to Apex I achieved the financial foundation that allowed me to begin investing on my own,” Zeev said. “Right now I have raised a total of a little over $2 billion in all my funds. I don’t view the money I’m paid as commission as it all goes back into the funds and I also don’t take a salary. This is a business model that doesn’t allow me to acquire a private jet or yacht, although I don’t think I would have bought these even if the money would go to me.”

Will you remain a lone wolf?

“Of course. Otherwise, I’ll just become like one of the 2,000 regular VC funds.”

What is the advantage of operating independently?

“The ability to move quickly of course, but not just that. The truly exceptional investments are those in which you think differently than others and break conventions. But how many conventions am I actually breaking if I needed to convince six partners in an investment committee to do something that the rest of the world thinks is a mistake? In my model, once I’ve convinced myself I’m done. This way there is a chance to build a market leader and some of my companies are that. No one did anything like Houzz or Tipalti when I went with them. I think the myth that VC is a team game is beginning to crack.”

The whole isn’t greater than the sum of its parts?

“In theory, because the partners in the fund help each other, but I claim otherwise. Investing is an individual sport. When I started 15 years ago it was very radical to do it on my own. But I don’t think there are advantages to a partnership. The thinking that partners will help you is simply not correct.”

“Because there is a certain level of competition between the partners and if you feel that you are providing all the value it bothers you. And if I wanted to invest but the partners killed the idea and the company ended up becoming Facebook? And on the other hand, if they did what you wanted and because of you, they lost money? The frustration between the partners builds up, but no one has any interest in expressing it. I promise you that there are many partners that can’t stand each other and don’t appreciate each other. Therefore, there is an advantage to being by yourself compared to being big. There are more like me these days, although as of now I’m the biggest and most successful lone investor in the world.”

How do you decide when to invest?

“I need to love the entrepreneur and the technology and at least one of them needs to be proven to a certain extent. I usually invest in older entrepreneurs. And for me, it is almost always love at first sight. If I need two weeks to be convinced it is probably not it. It happened once with my wife, but with companies, it happens to me all the time.”

“With Riverside, I didn’t even meet the entrepreneurs, but I had a phone call with them and that same day I told them ‘let’s talk tomorrow. I want to send you an offer’. They already had a draft with another investor. With most of my investments, I decided in less than 24 hours.”

You have a reputation for having a golden touch.

“Maybe it is the reputation, but the main reason for my success is that the right entrepreneurs want me. And the chances of that increase when it is an entrepreneur in my network. More than half of my investments come thanks to a connection between one of my entrepreneurs and other entrepreneurs, or when someone I trust tells me that someone is awesome. VCs publicize themselves as if they make companies great, but in fact, it is entrepreneurs who make the VCs great. One of the reasons that entrepreneurs love me is because I understand that. I’m not the story. They are the story.

“When good entrepreneurs want you because they believe you have a golden touch it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Despite living in Silicon Valley for the past two decades, Zeev noted that around 80% of his portfolio is of companies either headquartered in Israel or founded by Israelis.

“I think I have a crazy effect on Israeli high-tech, but I don’t want to claim that it is all due to Zionism. Being Israeli doesn’t drive my decisions and the reason that my portfolio is this way is mainly due to the fact that my network is very Israeli. I do a lot more for Israel when I’m living in the U.S. as when that’s the case I have a massive advantage over someone who is based in Israel.”

Does this occupation still excite you?

“This is my passion. No matter how many successes I have, I still want the next one. I’m sure Messi also doesn’t care how many goals he has scored and is always hungry to score the next goal.”

“To score one more goal, and then the next one. Did Leonardo da Vinci ever get fed up with painting? Warren Buffett is still doing his thing. I’m of course not comparing myself to them, but there is a similarity in regards to the passion.”