In 2013, the US investment bank Morgan Stanley dubbed Indonesia as one the “fragile five”, a group of emerging economies that it believed were especially vulnerable to a jump in interest rates in the US.

Almost a decade later, US interest rates are rising sharply, which is adding to the economic problems in the developing world. But Indonesia appears unruffled.

At a time when the global economy is being battered by the Ukraine war and the global energy, food and climate crises, Indonesia has emerged as an unlikely outlier, boasting both a booming economy and period of political stability.

Gross domestic product expanded 5.4 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter, well above forecasts. The country’s inflation rate at 4.7 per cent in August, prior to a recent petrol subsidy cut, is one of the lowest globally. Its currency, the rupiah, is among the best performing in Asia this year and its stock market is hitting record highs.

The resource-rich archipelago, south-east Asia’s largest country with 276mn people, is riding high on soaring commodity prices. Exports rose 30.2 per cent year-on-year to $27.9bn last month, the most on record. The world’s largest producer of nickel, a critical component in electric vehicle batteries, Indonesia is putting in place plans to benefit from the upcoming boom in EVs.

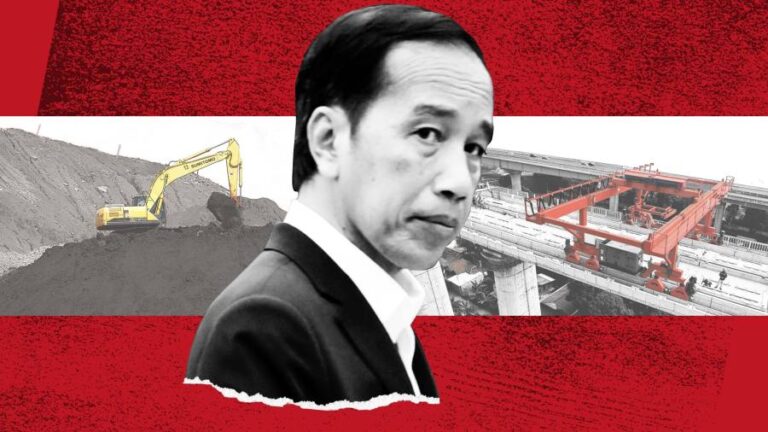

Much of the credit for this boom has gone to Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo, who has managed to maintain popularity with both ordinary Indonesians and investors alike after eight years in power. A poll released this week by research firm Indikator Politik Indonesia showed 62.6 per cent of Indonesians approved of the charismatic former furniture salesman’s performance, down about 10 percentage points since before the fuel subsidies were cut, but still leaving him as one of the world’s most popular democratic leaders.

Support for Widodo, who is known as “Jokowi”, is so strong that at one point his supporters were pushing to change the constitution to allow him to stand for a third term in office.

Widodo will have a chance to show off this prosperity to the world when he hosts the Group of 20 summit in Bali in November. He plans to use the event to court interest from global investors, including for his most ambitious and controversial plan yet — a more than $30bn proposal to shift Indonesia’s capital from Jakarta to the jungle-clad island of Borneo, a project that could yet decide his legacy.

“What we want to build is [a] future smart city based on forest and nature,” the president tells the Financial Times over a lunch of spicy soup and Japanese barbecue at the presidential palace in Jakarta, his face lighting up at the mention of the new capital. “This will showcase Indonesia’s transformation.”

But even as investors flock to see the new Indonesia, some worry about the sustainability of its newfound stability. Next year, campaigning begins for the 2024 election and Widodo does not yet have an anointed candidate to carry on his agenda. Critics also say he could have done more to further embed Indonesia’s young democratic institutions, leaving it vulnerable if a more venal leader comes to power in future.

“So many emerging markets have problems, Indonesia doesn’t have them right now. The economy is firing on all cylinders,” says Kevin O’Rourke, a Jakarta-based analyst on Indonesian politics and economics and principal at consultancy Reformasi Information Services.

“The problem is politics. We are 18 months from election day and that could present a stark contrast in Indonesia’s longer-term outlook. It could be good after 2024 or it could be quite bad.”

Political outsider comes good

The Widodo who will host world leaders at the G20 summit is almost unrecognisable from the humble former mayor of Solo, Central Java, where he started his political career 17 years ago. Although he retains some of his old pastimes, such as listening to heavy metal and riding motorbikes, he has emerged as an astute political tactician at the national level. A political outsider, Widodo has favoured “big tent” coalitions, bringing friends and foes alike into his cabinet.

George Yeo, Singapore’s former foreign minister, calls it “democracy with Javanese characteristics”.

“That is: ‘We will campaign like hell, we will call each other names, but when the ballots are counted and we all know what the relative proportions are, we will form a coalition cabinet . . . and you’ll get your share’.”

This, he argues, has led to Indonesia’s current stability. One example is Prabowo Subianto Djojohadikusumo, a controversial former army general who ran a fierce campaign against Widodo in 2018 but is now the minister for defence.

Investors say this political stability has helped the economy. With inflation relatively low, Indonesia’s central bank only raised interest rates for the first time in three years in August to 3.75 per cent. Banks are also still lending and exports are booming, not just from commodities. Widodo’s signature “omnibus law” that loosened employment regulations to help job creation has encouraged more foreign investment, as some producers diversify manufacturing away from China.

“You can see what Indonesia is exporting now, right across the board. You name it, textiles, garments, footwear, machinery, furniture, electronics, autos . . . things that create good jobs and incomes. This was the second year of double-digit, year-on-year growth,” said Reformasi’s O’Rourke, referring to Indonesia’s export earnings over the past several months.

Economists caution that Indonesia’s main commodity exports, such as coal and palm oil, still play a “big role” in driving growth. Commodity prices could start to lose steam this year as western economies slow down, says David Sumual, chief economist of Bank Central Asia in Jakarta.

“Next year will be quite a challenge,” he said. “That’s why I have downgraded my GDP forecast to below 5 per cent.”

Inflation, which has been suppressed by fuel subsidies, could also rise quickly to hit 8 per cent by October, according to Priyanka Kishore, chief economist for south-east Asia and India at Oxford Economics.

“The central bank has jumped on the global hiking cycle later, they may have to do a bit more, more quickly, to tackle inflation now,” she says.

Indonesia has introduced restrictions on some commodities, including taxes on coal and nickel, that have jolted markets. Yet they have also helped the development of its domestic processing and refining sectors.

“The headline is clearly that things are going well,” says Eugene Galbraith, director at mobile phone tower company PT Protelindo and a longtime observer of Indonesian business. “All those things, both good and bad policy decisions, on balance equate to a broadly popular and highly regarded president.”

Advantage in natural assets

One of Widodo’s principal achievements has been to expand infrastructure on an unprecedented scale for Indonesia, a vast country of 17,000 islands. His governments have constructed 2,042km of toll roads in eight years, he said, compared with about 780km in the prior 40 years, as well as 16 airports, 18 ports and 38 new dams. Costs have blown out on signature projects such as the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway — China’s first overseas high-speed bullet train project — while others have been poorly planned, with some shiny new airports in far-flung locations devoid of travellers. But the makeover is clearly visible, even to outsiders.

“I expected a change. But I didn’t expect such a change. Yes, there were traffic jams but they are not as bad as before,” the former Singaporean minister Yeo says of a recent visit to Indonesia. “Jakarta airport is better than any airport in the US.”

Yet by far the flagship industrial policy of Widodo’s second term has been his attempt to use Indonesia’s giant nickel reserves — which are tied with Australia as the world’s largest — to create a domestic electric vehicle industry.

In 2020, the government banned outright the export of nickel ore, forcing foreign companies, many of them Chinese, to begin refining it onshore. While most of the end-product is going into the stainless steel industry, the aim is to begin extracting more higher grade material for use in batteries. Indonesia is expected to provide a significant part of the new nickel supply needed by the global EV industry but its reserves of laterite ore require more processing.

Widodo credits the restrictions with lifting the value of nickel ore-related exports from $1.1bn annually five years ago to nearly $20.9bn last year.

“After [this], we can export maybe more than 40 times or 60 times [more],” he says. “Indonesia has the largest nickel reserves in the world, around 21mn tons, [or] around 30 per cent of world reserves.”

He adds that the next step could be to extend the policy to Indonesia’s large reserves of bauxite and copper. Demand for the materials, used for aluminium production and renewables, is also growing globally. While the EU has challenged the export restrictions for unfairly limiting access of European producers in the World Trade Organization, Widodo is unapologetic.

“It can create jobs for the people and give the added value for Indonesia,” he says.

The plan to refine Indonesian ore into battery-grade material is still just starting, with one refining plant commissioned in May last year and seven more in the pipeline, all on the island of Sulawesi, according to Isabelle Huber, a visiting fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Near Jakarta, South Korea’s LG Energy Solution and Hyundai Motor Group are building the country’s first electric vehicle battery cell plant while Hyundai is building an EV plant nearby. Indonesia says China’s CATL, the world’s biggest EV battery maker, has agreed to invest in an EV battery plant and Widodo said he was also wooing Tesla.

“Indonesia can still be a first mover and they’re lucky, they’ve got the most reserves [of nickel],” says James Bryson, director at PT HB Capital Partners, an investment advisory business.

The nickel industry, however, still faces problems. The most common process for producing battery-grade materials is through the high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) method, which produces the largest quantities of waste, known as tailings. Indonesia bans dumping of this toxic residue into the ocean while “dry stacking” these tailings is difficult in a high-rainfall tropical environment.

This could be an obstacle to supplying western markets, adds Bryson, as EU and US EV battery manufacturers “won’t be open to processes which produce tailings”.

Another potential problem is the use of dirty coal-fired power as energy for nickel processing plants. This will make it hard for batteries sourced from this nickel to be sold in the US and EU. Environmental groups have urged Elon Musk not to invest in Indonesia’s nickel industry for reasons including environmental damage.

The issues around nickel are part of a broader series of criticisms of the country’s environmental record. Local coal producers are able to supply 25 per cent of coal to local plants at a steep discount to market price, hindering the ability of renewable energy projects to be competitive, including solar, in a tropical country. “It is really economic development versus ESG,” said one foreign-based investor with business in the country.

Widodo’s other priorities have included the country’s education system and its bloated state-owned enterprises. In both, he has appointed well-known entrepreneurs or businessmen to lead the changes.

With other Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam aggressively vying to attract industries diversifying out of China, Widodo’s government needs to make Indonesia’s workforce more competitive and to modernise its state-owned companies, whose assets are the equivalent of half of GDP.

State-owned enterprises minister, Erick Thohir, who once owned Italian football team Inter Milan, says the reforms are urgently needed if Indonesia is to create enough jobs for its young population.

“If you look at the Indonesian population, it’s 270mn. The majority of our demographic is young. If they don’t get jobs, a country as big as Indonesia will create problems for the region,” says Thohir.

Corruption concerns

Widodo’s hosting of the G20 has thrust the question of the president’s legacy into the spotlight.

Investors worry that he has no clear political successor as the 2024 election draws closer. Lacking his own political party, he has so far been unable to clinch a nomination from a political party for his apparent preferred candidate, Central Java governor Ganjar Pranowo. “Ganjar has yet to be nominated by a party and every party already has a candidate. He’s an emperor without an empire,” says PT Protelindo’s Galbraith.

Critics also say that under Widodo, the powers of Indonesia’s once formidable Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) have been weakened. The commission’s personnel were converted from staff of an independent agency to civil servants in 2019, undermining the body’s autonomy from the government, critics claim. Last year, Indonesia scored 38 out of 100 on a widely used corruption index by global group Transparency International, on a par with Brazil and lower than India, Vietnam and China.

5.4%

Year on year expansion of GDP in the second quarter of 2022

16

Airports built during the presidency of Joko Widodo, as well as 18 ports and 38 dams

2,042km

Distance of new roads built in Indonesia in the same period

Widodo insisted that the KPK remains independent and pointed to fines and jail time for politicians in recent years.

The president also has failed to undo hundreds of regulations mostly introduced under predecessors that discriminate against religious minorities, LGBT individuals and women, such as those compelling use of the veil for girls at school, said Andreas Harsono of Human Rights Watch.

“Jokowi doesn’t care as much about democracy or democratic reforms, such as the space for independent journalism or civil society. There is still a basic understanding of free and fair and competitive elections but the space for criticism has been restricted,” says another Indonesia analyst, speaking anonymously for fear of repercussions.

Utopian visions of a new capital

Yet the issue that could decide the president’s long-term legacy — for better or for worse — is Nusantara, the new capital. The project’s proponents say flood-prone Jakarta is sinking, in some areas by 25cm per year, and that Indonesia needs to spread its development beyond the main island of Java, which accounts for 56 per cent of the population and a similar portion of the economy.

Nusantara will be three and a half times the size of Singapore and four times larger than Jakarta. The first phase of the project, which entails moving the presidential palace, the vice-presidential palace, armed forces, the police and other ministries by 2024, is being funded by the government. The development is slated to be completed by the country’s centennial in 2045, when Indonesia hopes to be the world’s fourth-biggest economy.

Bambang Susantono, a former Asian Development Bank official who was appointed chair of the Nusantara Capital City Authority this year, puts the cost for this first stage at “more than Rp50tn [$3.3bn]”, but insists this will not all be public money.

“We are developing with a state-owned budget because we need to create market confidence,” he says. “[But] the interest from the private sector is there.”

Critics counter that building infrastructure on Borneo’s peatland is tricky, while moving tens of thousands of troops and building new military facilities for them is expensive. About 80 per cent of the project was meant to be funded by private capital, which is yet to materialise. One high-profile backer, Japan’s SoftBank, pulled out this year.

“I am sceptical that it can be done in the next few years,” says Evan Laksmana, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore.

Others argue Widodo will get the project to a point where it has to proceed. “Nusantara will be too big to fail,” says Fajar Hirawan, a researcher at the Department of Economics, Center for Strategic and International Studies.

But Widodo, who says he plans to dote on his five grandchildren and work with “nature” when he steps down in 2024, is adamant about the urgency of building the new capital.

The new capital is needed to ensure that development spreads beyond Java “so that progress can be [enjoyed] by all”, he says.