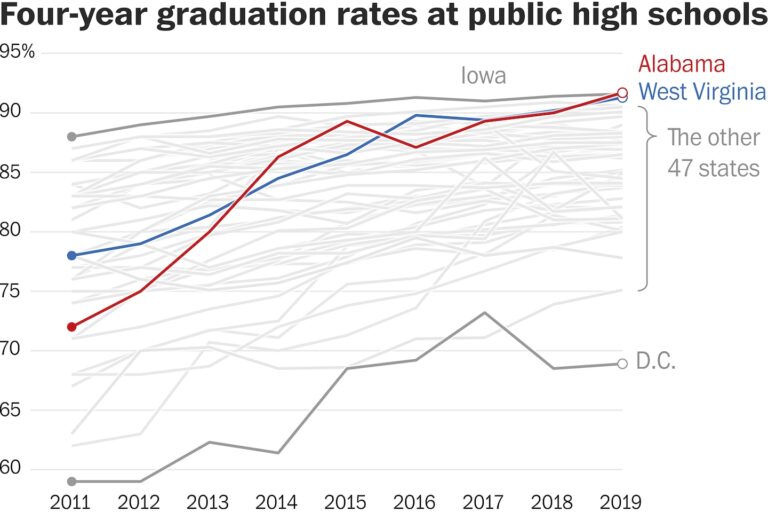

Between the 2010-2011 school year, the first for which we have consistent data from the National Center for Education Statistics, and 2018-2019, Alabama and West Virginia launched themselves from 40th and 27th in the nation in the rate of students who graduated from high school in four years to first and third, respectively, joining No. 2 Iowa at this pinnacle of education achievement. (Data since the pandemic, which scrambled public school schedules and standards, is not yet available.)

What’s behind this apparent public education miracle? Our embarrassingly glib answer is, of course, data. After all, it would’ve been tough to make that chart without it. But on closer examination, that answer may be less glib than it sounds.

Until the past decade, nobody knew how well state school systems were doing in terms of graduation rates. States reported their own metrics with their own definitions of graduates and dropouts, and comparisons between states were difficult.

This proved inconvenient for policymakers who — after years of fussing over test scores — began to realize that graduation mattered even more. And its importance has increased with every passing year: In the mid-1970s, a high school dropout could earn almost three-quarters of the U.S. median wage. By the early 2000s, that figured had plummeted to about half.

So in 2008, at the tail end of the George W. Bush administration, an update to Bush’s signature No Child Left Behind initiative required states to follow a consistent process for measuring and reporting graduation rates and set ambitious targets for improving them over time.

Unlike the school-based testing requirements that initially formed the controversial backbone of No Child Left Behind, the new focus on graduation appears to have worked. The once-stagnant graduation rate rose substantially over the following decade.

“It seems like the greatest success story of NCLB,” said Tulane University economist Douglas Harris, director of the National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice.

Calling it “probably the most positive result that we have for accountability, period,” Harris pointed out that while we all obsessed over test scores, transformative results were quietly piling up in a metric that wasn’t even an initial goal of NCLB. And, as our glib answer above implied, simple, inexpensive data collection really did drive the transformation.

“We don’t have many policy levers that can increase these outcomes without a substantial financial cost,” Harris said. “For graduation rates, accountability seems to be one of those levers.”

West Virginia and Alabama were some of the earliest, most enthusiastic and most persistent adopters of graduation-rate targeting, said Robert Balfanz, director of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University.

“They took it seriously as a state-level problem, often with the involvement of the governor and the state Department of Education,” Balfanz said, “and they made it a priority over quite a long period of time.”

In particular, the two states focused on what Balfanz called an early warning system, tracking behavior, attendance and grades in the ninth grade, a critical point at which many future dropouts fall through the cracks in the transition from middle school to high school.

While some students leave because they got a job or got pregnant, Balfanz said, “the biggest number of kids dropping out were the kids who were falling behind in ninth grade and not catching up.”

Both states worked with outside vendors to track vulnerable students and to share detailed data with their teachers. This data-driven approach allowed teachers to target specific students and figure out what was keeping them out of class or causing them to fail, whether it be work, family, bullies or social isolation. It was “nothing dramatic,” Balfanz said. “Just lots of problem-solving and small efforts that help students stay on track.”

To be sure, there are reasons to be skeptical of the sudden improvement. As economists often say, when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

“In general, people don’t suddenly get better at their jobs, so sudden improvements in measures usually mean they are misleading,” Harris said. “That said, part of the good news here is that the increase was fairly gradual.”

The numbers themselves seem solid: A Post analysis of census data shows the share of 19-year-olds with diplomas closely tracks the trend in reported graduation rates over the period for which they’re available.

And the big jump in performance in Alabama and West Virginia doesn’t seem impossible. While the Census Bureau data isn’t quite as dramatic, our analysis found that both states ranked comfortably near the top for fastest growth in the share of young people with high school diplomas over the past decade.

Harris nonetheless initially maintained a healthy skepticism of NCLB’s quiet graduation-rate revelation. So, in a recent Brookings analysis with his Tulane colleagues Lihan Liu and Nathan Barrett, and Ruoxi Li, now a PhD candidate at Yale University, Harris looked at several possible means by which schools could game the system. They found no smoking gun, at least at the state level.

Most schools don’t seem to be cutting corners, they found: In fact, many of the gains occurred as schools were also trying to raise test scores to meet NCLB standards, which would typically depress graduation rates.

It seems possible that Alabama goosed its graduation rate by axing a required pre-graduation exit exam in 2013, a common move as states realized that such exams hurt the most vulnerable students without providing any clear benefit. Alabama ditched the exam as part of a shift toward more practical measurements of college and career readiness, such as earning an AP credit or obtaining a professional certification. Those measurements, as it happens, have just been enshrined as a new graduation requirement, starting with the class of 2028.

“What we ended up having over the last several years was a graduation rate that has been slowly ticking up because there was no longer that exam between you and graduation,” said Mark Dixon, president of A+ Education Partnership, an Alabama nonprofit advocate.

But it wasn’t smoke and mirrors, Dixon said. Alabama made measurable improvements to career readiness even as graduation rates rose. And Harris and his colleagues found that states with exit exams actually saw a slightly larger increase in graduation rates than states that didn’t have such exams, or states that abolished them.

When we talked as he was leaving the gym and getting ready to head out to a Saturday football game, Harris also made a surprising point: If the graduation-rate targets caused some districts to lower standards, there could be a silver lining.

Sure, students may lose specific knowledge if they are quietly passed in a home economics course they were about to fail, or allowed to make up a failed English class with an easy credit-recovery program. But their lost knowledge in those subjects may be less important than the knowledge they gain in other subjects simply by staying in school.

“Even if there was some relaxation of standards where they’re giving D’s instead of F’s, that’s keeping kids in school longer,” Harris said. “There’s more class time — they’re taking more courses as a result.”

Those courses may be producing a more skilled workforce and a more informed electorate — even if high school diplomas are a little bit easier to come by.

Hi! The Department of Data lives and dies by reader questions! Which states have the highest graduation rates for kids in foster care? How much could Bill Gates make from record farmland prices? What are the biggest causes of death in each U.S. county? Just ask!

To get every question, answer and factoid in your inbox as soon as we publish, sign up here. If your question inspires a column, we’ll send an official Department of Data button and ID card.