1. Why the war over chips?

Chipmaking has become an increasingly precarious business. New plants have a price tag of more than $20 billion, take years to build and need to be run flat-out for 24 hours a day to turn a profit. The scale required has reduced the number of companies with leading-edge technology to just three — Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), South Korea’s Samsung Electronics Co. and Intel Corp. of the US. Chipmakers have been under increasing scrutiny over what they sell to China, the largest market for chips. National security concerns, shifts in the global supply chain and the pandemic-era shortages led governments from the US and Europe to China and Japan to subsidize investment in new production lines costing tens of billions of dollars. More recently, slowing economies have curbed global demand, causing a glut of unwanted chips.

2. Why are chips so critical?

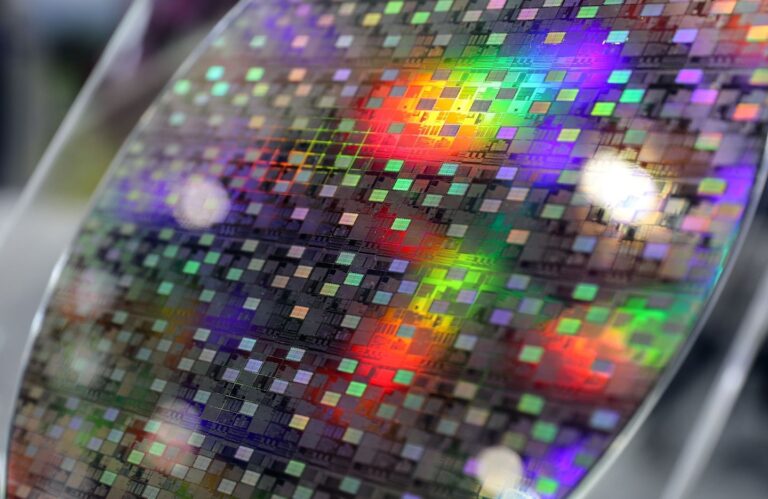

They’re what’s needed to process and understand the mountains of data that have come to rival oil as the lifeblood of the economy. Made from materials deposited on disks of silicon, chips can perform a variety of functions. Memory chips, which store data, are relatively simple and are traded like commodities. Logic chips, which run programs and act as the brains of a device, are more complex and expensive. As the technology running devices — from rockets to refrigerators — is getting smarter and more connected, semiconductors are ever more pervasive. That explosion has some analysts forecasting that the industry will double in value this decade. Spending on research and development for chips is dominated by US companies, with more than half the total.

3. How did we go from chip shortages to a glut?

Pandemic lockdowns and supply chain disruption made many types of chips scarce for about two years. With demand for phones and personal computers cooling off post-pandemic, the cycle has turned. PC and smartphone makers have slashed orders for chips as consumers tighten the purse strings, and there’s oversupply in areas such as industrial machinery and cloud computing. The chipmakers are responding by reining in their plans for new production capacity, even though governments are willing to foot part of the bill.

4. How’s the geopolitical competition going?

• In October, the US imposed tighter export controls on some chips and chipmaking equipment to stop China from developing capabilities that could become a military threat, such as supercomputers and artificial intelligence.

• The success of Washington’s containment policy around China depends partly on getting allies to impose similar restrictions on their local companies. The effort appeared to be paying off in early 2023, with Japan and the Netherlands agreeing to join the US in limiting China’s access to their advanced semiconductor machinery.

• China’s chipmakers still depend on US technology, and their access is shrinking. A huge Chinese spending spree hasn’t succeeded at creating sufficient domestic supply of vital components.

• US politicians have decided that they need to do more than just hold back China. The Chips and Science Act, signed into law on Aug. 9, will provide about $50 billion of federal money to support US production of semiconductors and foster a skilled workforce needed by the industry. All three of the biggest makers have announced plans for new US plants.

• Europe has joined the race to reduce the concentration of production in East Asia. European Union nations agreed in November on a €43 billion ($46.6 billion) plan to jump-start the region’s semiconductor output. The goal is to double production in the bloc to 20% of the global market by 2030.

5. How does Taiwan fit into all this?

The island democracy emerged as the dominant player in outsourced chipmaking partly because of a government decision in the 1970s to promote the electronics industry. TSMC almost single-handedly created the business of building chips designed by others, one that was embraced as the cost of new plants skyrocketed. Big customers like Apple Inc. gave TSMC the massive volume to build industry-leading expertise, and now the world relies on it. The company overtook Intel in terms of revenue in 2022. Matching its scale and skills would take years and cost a fortune. Politics have made the race about more than money, though, with the US signaling it will continue efforts to restrict China’s access to American-designed chips made in Taiwan’s foundries. China has long claimed the island, just 100 miles off its coast, as its own territory and threatened to invade to prevent its formal independence.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com