Bengaluru: When intense rains reduced parts of Bengaluru into a sort of dystopian Venice earlier this month, with drenched people traversing the streets on boats, residents of some parts of the city found it much easier to wring themselves dry, thanks to a “model” stormwater drain.

Originating near the Majestic area and flowing into the Bellandur Lake (which flooded after the deluge) the Koramangala valley stormwater drain — or K-100 — is an outlier in a city known for its silt-filled drainage infrastructure.

Unlike most of its clogged counterparts, the 12 km drain (which is not fully rejuvenated yet) was able to do its job on the intervening night of 4 and 5 September when the city drowned in 131.6 mm of rain.

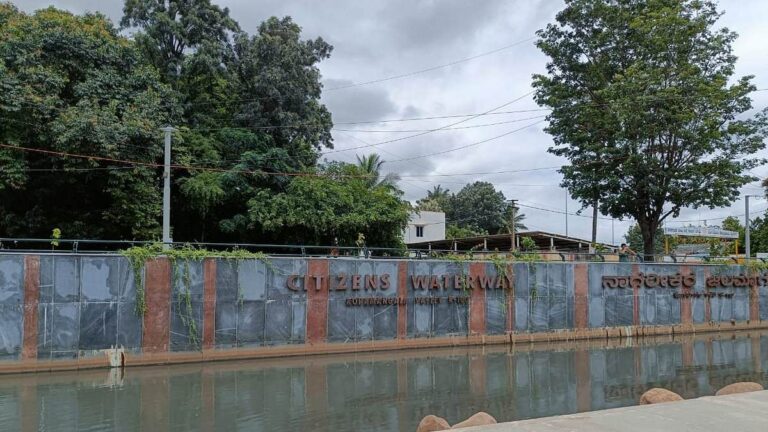

When ThePrint visited Tuesday, the area around the drain near Shanti Nagar bus station, which is the first phase of the project, looked scenic, with a spacious arena, attractive plants, and writing that read “Citizens Waterway” on the walls. Two men could be seen sauntering across a short bridge and along a walkway before ascending the stairs to the other side.

Just two or so years ago, the drain was not much more than a garbage-clogged sewer, but it got a new lease of life when the Karnataka government — inspired by Seoul’s renewal of the 10.9 km concrete-covered Cheonggyecheon stream — decided to upgrade it, under the aegis of the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), the city’s civic body.

The results have not been just aesthetic.

“The whole drain held up pretty well during last week’s rainfall except maybe for one spot where the bund was incomplete,” city architect Naresh Narasimhan from the Mod Foundation, who conceptualised this BBMP project, told ThePrint.

The K-100 drain passes via KR Market, Shanti Nagar, Hosur Road, Ejipura, National Games Village, Koramangala, ST Bed layout and culminates at Bellandur. Its watershed spans 32 sq km, and it carries a twelfth of the city’s sewage/runoff.

“The water was flowing nicely even while travelling through the old city. Now all the bridges are in one span, the waterway is clean, there is no silt or solid waste. People are also getting more disciplined and not throwing plastic into the drain since there are more tippers available along the stretch,” Narasimhan added.

Today, the K-100 project is being held up as a pilot project that can be scaled up to help protect Bengaluru from floods. Since it flows through different strata of land use under a range of conditions, the project offers inputs on how to adapt it to various conditions in a city with a burgeoning population.

Also read: Heavy rain, poor drainage, worse infra — how Bengaluru was hit by a perfect storm and drowned

How the project started

In 2016, in a landmark judgment, the National Green Tribunal quashed the environmental clearance and plans sanctioned for a Rs 2,300 crore project on the Bellandur Lake wetland. Apart from staying the construction, the green court asked for 3.10 acres of lake land to be reclaimed and multiple rajakaluves or stormwater drains to be restored.

When the NGT ordered the de-concretisation of the drain’s entire length, the civic authorities began mulling over ways to rejuvenate the stretch.

The BBMP took up the project to rejuvenate K-100 with the help of urban designers and architects at Bengaluru-based Mod Foundation.

According to B.S. Prahalad, BBMP engineering chief, Rs 150-160 crore has been spent on the project so far, which is aimed at “bringing back 32 acres of public space worth Rs 1200 crore”.

But the project was not without its difficulties.

When the team began work on rejuvenating the stormwater drain, it resembled an open sewer. There was lots of indiscriminate dumping of garbage, properties running alongside the drain emptied their waste directly into it, and industrial effluents mixed with sewage and rainwater.

“The biggest challenge which we faced in K-100 was reworking the pipe drainage system from open flow to piped flow. We were able to divert sewage away from the drains and 900 trucks of silt were removed,” Prahalad said.

Eventually, he said, the team was able to restore the earlier gradient, which had changed because human waste flowing into stormwater drains had deposited 2 metres of silt. With this extra silt gone, the drainage system was able to flow smoothly.

“Before this, areas along the drain, including Koramangala, were getting flooded every year,” he said.

Restoring Bengaluru’s ‘water heritage’, with public help

With Bengaluru urbanising at a fast pace, the original rajakaluves or traditional irrigation canals like K-100 have narrowed down and are choked with bottlenecks.

Prahalad believes that replicating the process used for K-100 in these canals could yield great results, but it will also need buy-in from the people.

“[K-100] is definitely a model. But first of all, the public should come forward and say that our rajakaluves should be sewage-free. If sewage is removed from stormwater drains, we can go in for desilting and have an artificial river. If groundwater enrichment happens it will help in reducing floods and we can bring back the glory of the river system in this city,” he said.

Nidhi Bhatnagar, an urban designer from the Mod Foundation, also said that the premise of the project was to connect the city and its people to their “water heritage”, but that many are unaware it even exists.

“If you don’t know there is a water body flowing in a specific place since it is fenced off, how do you even let people know that this is something that is theirs?” she asked.

For inspiration, the team looked at examples from China, Korea, and the Philippines.

One aspect that stood out was that public participation is a key aspect of the success of waterway renewal projects.

“What was interesting about the [renewal of the] Pasig River in Manila was that it was quite charged with public participation,” said Narasimhan.

In the K-100 project, several city and state agencies worked together and collaborated to create awareness amongst people living on either side of the drain.

Now, communities contribute plants to the planters lined along the walls and enjoy the open spaces. In the years the project has been running, the team has seen a significant reduction of sewage and waste going into the stormwater drain.

“Unless you take out the sewage, the solid waste, and the silt out of existing drains, no scheme will work. All you have to do is this, and 80 per cent of the problem will be resolved,” said Narasimhan. “Encroachment is one part of it. The real bigger problem is silt, solid waste and sewage and the need to keep widening the width of the channel as you go along.”

Narasimhan added that sifting through examples from other countries revealed the importance of natural water systems to remediate drains and the use of artificial wetlands to clean and filter the water.

“This is an important thing we need to bring to India, it is called constructed wetlands,” said Narasimhan. “We often assume that the only way to treat wastewater or liquid waste is through expensive membrane-based water treatment plants which need electricity and dosing of chemicals.”

“The guiding principle of this project was that we have to move from a grey to a green infrastructure paradigm. We must bring the public into public infrastructure,” the architect further said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also read: ‘Convenient to blame outsiders for floods’ — Bengaluru residents lament ‘blame game’ politics