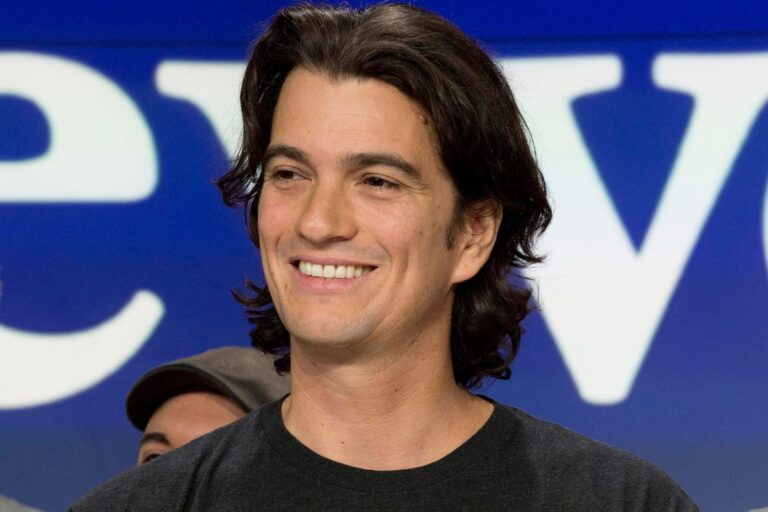

FILE – In this Jan. 16, 2018 file photo, Adam Neumann, co-founder and CEO of WeWork, attends the … [+]

Venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz is reportedly investing $350 million in Flow

FLOW2

NYT

WeWork’s initial valuation in 2017 was $20 million. This peaked at $47 billion before a swift, colossal plunge. Today, it is valued at around $4 billion. Much of the co-working office space company’s troubles have been attributed to Neumann’s bad decisions and reckless leadership style. He was ousted from WeWork in 2019.

How does someone who was so publicly fired walk away with $200 million in cash and $245 million in company stock for himself and then secure such a lucrative deal less than three years later from an elite Silicon Valley venture capital firm? It could be Neumann’s good ideas. But it is also Neumann’s privilege. A privilege that isn’t equitably distributed.

Research consistently shows that Black entrepreneurs, especially Black women, are systematically disadvantaged by underinvestment in their startups. For instance, a 2020 McKinsey report notes that white entrepreneurs start businesses with approximately three times more capital than Black business owners: $107,000 versus $35,000. Similar inequities also stifle other entrepreneurs of color and white women. Even if their ideas are good (and perhaps substantively better and financially more profitable than Neumann’s), diverse innovators are often deemed too risky or not sufficiently proven. Ironically, Neumann’s failure has been proven.

In an announcement on its website yesterday, a16z co-founder Marc Andreessen wrote, “we love seeing repeat-founders build on past successes by growing from lessons learned. For Adam, the successes and lessons are plenty and we are excited to go on this journey with him and his colleagues building the future of living.” At least three things about this are noteworthy.

First, too few entrepreneurs of color and women are afforded opportunities to become repeat-founders, even when their first startups are successful. In other words, getting their first businesses launched is challenging because of investment inequities. Those inequities snowball as guys like Neumann get rounds and rounds of funding for multiple business ideas.

Characterizing Neumann’s prior leadership as “success” is another notable aspect of the a16z co-founder’s statement. Neumann failed to take WeWork public. Its valuation significantly plummeted under his leadership. He and his wife allegedly engaged in lavish spending at WeWork’s expense. Employees deemed the workplace culture toxic. All this is extremely well known, as Neumann and the company have been subjects of the Apple TV+ series WeCrashed, multiple books, business school case studies, expert analyses, and perhaps way too many commentaries.

Women and entrepreneurs of color don’t get to fail in such grand fashions and then subsequently convince investors to trust them with millions more.

The inequitable distribution of second chances isn’t restricted to failed startups. It occurs across industries and has a disproportionately negative effect on the careers of diverse professionals.

For example, let’s take higher education, an industry in which several head football and men’s basketball coaches in major athletics conferences earn multimillion-dollar salaries. Black coaches are severely underrepresented. But even when they are afforded head coaching opportunities, they are given shorter timeframes than their white counterparts are to turn around underperforming teams. In other words, Black coaches get fired more quickly. Also, securing another head coaching job at the highest level rarely happens for them.

As entrepreneurs go, WeWork’s failed head coach has been given a financially-lucrative second chance that surely wouldn’t have been extended to a Latina who’d delivered similar results.

Andreessen’s claim that the “lessons are plenty” for Neumann is also fascinating. It’s highly likely that most diverse entrepreneurs who failed or were driven out of their companies for poor leadership learned a lot. This may be the case for Neumann, too. The difference, though, is that he hopefully gets to learn from past mistakes as he launches Flow. Underrepresented business leaders who failed aren’t usually afforded such opportunities to demonstrate that they’ve learned or to apply lessons from prior failures to new, well-funded startups.

Ultimately, Andreessen Horowitz gets to determine in whom and in what to invest its capital. But $350 million sure could make a massive difference in the lives and businesses of entrepreneurs of color and women who haven’t failed in the ways Neumann has.

Venture capital firms really ought to stop contradicting themselves by claiming that diverse startups are too risky, yet invest tremendously in entrepreneurs like Neumann who’ve actually failed big.