Introduction

A systematic review in South East Asian countries has highlighted gaps in Myanmar mental health policy and its implementation, in particular the lack of trained human resources and the need to deliver community-based care.

Krishnan AKI, N P, Mohan R, Stein C, Sandar WP. Evidence on mental health policy gaps in South East Asia: a systematic review of South East Asian countries with special focus on Myanmar. In Review, 2020. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.20080/v1. Accessed 21 October 2021.

Although limited, incomplete, and sometimes equivocal data have been published regarding the prevalence of mental disorders in Myanmar,,

two community-based surveys were conducted in 2004, and reported point prevalence for all mental disorders of 7·7% and 8·6% (0·55% and 0·6% for psychoses, 3·8% and 4·1% for anxiety disorders, 0·5 and 0·57 % for depression, respectively in each survey).

For epilepsy, data have been published as part of the recent Myanmar Epilepsy Initiative led by the World Health Organization (WHO), and have shown a prevalence of epilepsy ranging from 0·83 to 1·90 per 1000 population depending on the township.

Despite their high prevalence, mental disorders and epilepsy are under-diagnosed and under-treated in Myanmar. The treatment gap is high for both: up to 95·8% for psychoses,

and 95·0% for epilepsy. There are several barriers limiting access to mental health and epilepsy care in LMICs, particularly in Myanmar. The budget allocated to mental health in Myanmar is very low with only 0·36% of total health budget dedicated to it, and 75% of the mental health budget is allocated to psychiatric hospitals.

In addition, there are very few healthcare professionals specialized in mental health or epilepsy (1·2 trained mental health workers per 100,000 people), and these are based in the main cities while 70% of the population lives in rural areas. Primary healthcare workers receive insufficient training regarding mental health or epilepsy during their curriculum, leaving them ill-equipped to manage patients with mental disorders or epilepsy.,

Moreover, there is very low awareness and understanding of mental disorders and epilepsy among the population, with many false beliefs and prejudices surrounding these disorders within the community.

,

This project combined an integrated approach at the community level including the training of frontline health workers (community health workers (CHWs) and general practitioners (GPs)) and raising awareness among the population, with the use of low-cost new technologies (smartphone, tablet), to improve the identification, diagnosis and management of people with mental disorders and epilepsy.

GPs who work in private healthcare facilities provide curative and other health services in parallel to the public sector.

The general objective of this community-based study was to assess the effects of a series of activities implemented by the Myanmar Medical Association over a 2-year period in Hlaing Thar Yar Township involving CHWs and GPs on the identification, diagnosis and management of people with psychotic disorders, depression and epilepsy.

- –

Evaluate the prevalence, the treatment gap, and assess the barriers to treatment;

- –

Monitor patients flow between CHWs and GPs, and assess the adequacy of treatment prescribed by trained GPs;

- –

Evaluate the effects of the intervention on the knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) among CHWs, GPs and general population.

Methods

Program overview

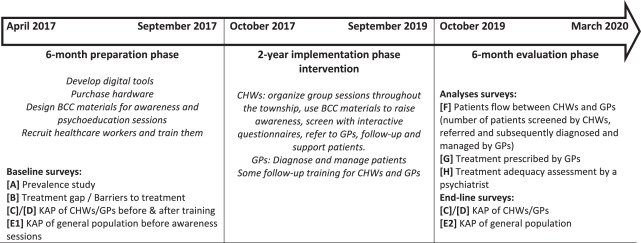

Figure 1Program overview.

Figure 2Location of Yangon and Hlaing Thar Yar Township in Myanmar.

GPs did not receive any remuneration to participate in the study. CHWs received a token amount approximately equivalent to USD 25 per month.

The project protocol in Appendix 1 provides additional information regarding the various interventions and surveys.

Study population

Participants aged 18 years and over, who had lived in Hlaing Thar Yar for a minimum period of 6 months at the time of the survey, were included in the general population surveys [A] and [E1], while for [B], people had to be identified with a psychotic disorder, depression or epilepsy. People who refused to participate, who were seriously ill or unable to speak were not included. A total of 3,100 people was the minimum sample needed for [A], [B] and [E1] surveys.

In the patient flow analysis [F], suspected cases who were identified by participating CHWs as potentially having a mental disorder or epilepsy and were referred to a GP, and patients who were diagnosed by GPs between October 2017 and September 2019 were included. In the analyses about treatments prescribed [G], and treatment adequacy [H], patients diagnosed between October 2017 and September 2019 with a psychotic disorder, depression or epilepsy by participating GPs and who had visits recorded in the database were included, except people who refused to participate.

In KAP surveys for CHWs [C] and GPs [D], all CHWs and GPs who took part in the Myanmar Medical Association Hlaing Thar Yar mental health project and who completed the mental health and epilepsy training in September 2017 were included, and those who refused to participate or left the project were not included. To detect the effect of awareness sessions on KAP in the [E2] survey, 205 subjects were required.

The sample size calculation and sampling procedures are detailed in Appendix 1.

Data collection

The screening questionnaires used in survey [A] were based on the PHQ9 for depression, on the PSQ for psychotic disorders, and on the Manual on Epilepsy for Medical Officers by Epilepsy Initiative, Myanmar for epilepsy, and modified according to local context. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants and data regarding their KAP on mental disorders and epilepsy [E1] and [E2], as well as their perceptions regarding barriers to treatments [B] were collected through face-to-face interviews.

The results from the screening by CHWs were captured through the questionnaires available on their smartphone; data regarding visits, diagnosis made by GPs and treatment prescribed at each visit, were captured by GPs on their electronic tablet. Treatment adequacy was retrospectively assessed by a senior psychiatrist. The psychiatrist determined, based on the information available in the database (clinical history, symptoms, diagnosis made, time of diagnosis, treatment prescribed and dosage, severity of the disease and any other detail recorded by the GP at each visit) whether the treatment prescribed was: adequate / not adequate / not possible to evaluate.

In survey [C], the KAP self-administered questionnaire used with CHWs was the same questionnaire as the one used in the general population [E1] & [E2].

The self-administered questionnaire filled by GPs for survey [D] included 106 questions based on the content of the training course and regarding their knowledge and attitudes about epilepsy, psychosis and depression.

Several endpoints were evaluated: number of patients identified by CHWs, diagnosed and managed by GPs, percentage of concordance between CHWs’ screening and GPs’ diagnosis, percentage of adequate treatments prescribed, and the evolution in KAP after training for CHWs, and GPs, and after the 2-year intervention for health workers and the general population, for which an increase in score was a sign of improved KAP.

More information on the details of the questionnaires and the calculated scores can be found in Appendix 1.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 20). For descriptive analysis, numbers and percentages were used for qualitative variables, and means and standard deviation for quantitative variables.

Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare qualitative variables. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare means between two independent groups. Wilcoxon test was used to compare means between two dependent groups. Pearson correlation was used to evaluate association between two quantitative variables.

A coefficient kappa was used to measure the agreement between CHWs’ screening and GPs’ diagnosis. A comparison between scores and sub-scores before and after training was done using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. For the comparison of scores post-training and post-intervention for CHWs and GPs, the Mann-Whitney test was used.

Variables with a p-value <0·2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis and a backward linear regression model was performed to identify factors associated with KAP score in the general population.

A reliability of instruments used in this study was evaluated by Cronbach alpha. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test a normality of quantitative variables.

A p-value ≤ 0·05 was considered significant throughout the study. Detailed statistical analysis can be found in Appendix 1.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approvals were granted by the Research Ethics Committee from the Department of Medical Research (2017/090) and by the Institutional Review Board from the Myanmar Medical Research Department (2020/025). All participants were informed about the research and signed a consent form.

Role of the funding source

Sanofi Global Health was involved in the design of the study, in the interpretation of data and the writing of the manuscript. However academic authors retained full control of data analysis, interpretation and decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

The baseline status of the Hlaing Thar Yar population was assessed prior to the intervention with 3,438 people being interviewed. The prevalence was estimated at 0·9% for depression, 0·84% for psychosis and 0·55% for epilepsy (Appendix 2, table S.1).

Overall, the average treatment gap was 79·7% with the highest treatment gap being for depression (90·3% of people with depression were not treated), (Appendix 2, table S.1). The majority of people in this prevalence survey were female, married, with low level of education, and without employment. Among the people with illness, men (p = 0·045), people with low education level (p = 0·02), and with a low monthly income (p < 0·001) were over-represented, whilst there was a greater proportion of married people (p < 0·001) among people without illness (Appendix 3, table S.2). Overall, for people suffering from one of the targeted disorders, among the barriers to treatment, the two most frequently mentioned were “couldn’t afford to take treatment” (69·6%), and “No proper knowledge about the disease” (59·5%) (Appendix 4, table S.3).

Implementation phase: patients’ identification, diagnosis and management

Screening and diagnosis

Figure 3Flow chart of patients in the database monitoring.

Management and adequacy of treatment

Approximately 10% of people with depression, psychosis, or epilepsy were not prescribed any pharmacological treatment. Monotherapy (treatment with a single drug) was the most widely adopted approach for the management of epilepsy (54·0%) and depression (36·7%), while 25·9% of patients with psychosis were treated with polytherapy (treatment with two or more drugs used at the same time) (Appendix 6, Table S.5).

For patients diagnosed with depression, sertraline was the most commonly prescribed (28·7% of visits), followed by escitalopram (18·9%) and diazepam (14·1%), whilst olanzapine (19·9%) was mainly used in combination therapy. For patients diagnosed with psychosis, olanzapine was the most commonly prescribed (28·6% of visits), followed by risperidone (18·1%), whilst sodium valproate (23·7%) was mainly used in combination therapy. For people with epilepsy, sodium valproate was prescribed in 56·7% of visits mainly as a single agent, followed by carbamazepine (27·6%) (Appendix 6, table S.6).

Table 1Treatment adequacy for all patients.

NA = data not available.

During the first visit, the treatment adequacy was higher for patients with subsequent follow-up by GPs compared to those with only one visit (77·7% vs 70·9%; p < 0·001). At the first and last visit, those with multiple visits showed a lower rate of inadequacy compared to those with only one visit (2·4% vs. 7·1%; 1·5% vs. 7·1% respectively; p < 0·001) (Appendix 7, table S.7).

Evolution of KAP

CHWs

Table 2Evolution of KAP scores for CHWs.

GPs

Table 3Evolution of KAP score for GPs.

General population

There was a greater proportion of men (p = 0·01), and people with a higher level of education (p < 0·001) in the group recruited at end-line, whilst there was a greater proportion of unemployed (p < 0·001) in the baseline group (Appendix 9, table S.9).

At baseline, the total KAP score was low. It didn’t differ significantly though between people with illness and those without illness. People with illness had a higher practices score (6·6 vs 5·2; p = 0·005) (Appendix 9, table S.10).

Table 4Difference of KAP score between baseline and endline of the general population.

Discussion

The treatment gap at baseline was high, particularly for depression (90·3%). Among suspected cases referred by CHWs, 86% saw a GP and 92% of them were diagnosed with one of the three disorders. The concordance between GPs’ diagnosis and CHWs’ screening was 75·6% overall. Attitudes and practices improved in the general population. For CHWs, knowledge improved post-training whilst attitudes and practices improved post-intervention. GPs’ global KAP score improved post-training and remained stable post-intervention.

,

,

Similarly, a systematic review in South Asia showed a prevalence of depression at 26·4%.

The rate of detection of depression in primary care in Myanmar is suboptimal, especially in comparison with the prevalence of depression in other countries in the same region,

,

,

related to the fact that depression is the least recognized and one of the most difficult mental disorders to identify., In addition, the screening questionnaire used in the prevalence survey was derived from the PHQ9 which is not validated in Myanmar. Development and validation of screening instruments is one of the priorities for research in low-resource settings in order to facilitate identification, and management of patients by non-specialist workers.

,

, ,

,

,

In addition, our evaluation after the 2-year implementation phase showed an improvement in CHWs’ attitudes and practices, with maintenance of the competencies acquired by GPs. Also, in India, training for CHWs improved their ability to recognize mental disorders post- training, which was sustained at the three-month follow-up assessment.

In Hong Kong, the number of patients with mental disorders seen per week, and percentage of patients treated was higher for trained GPs than for non-trained GPs.

In Mali, knowledge scores for GPs increased after first training, and increased further after the second training.

In Ethiopia, participants showed a significant increase in their KAP post-training.

After seven months of training in Bangladesh by WHO mhGAP, an improvement in knowledge and skills was reported.

In Pakistan, a 5-day face-to-face multi-method teaching program showed an improvement in knowledge to manage mental health diseases by role plays, videos and slide presentations.

In Finland, 40·9% received minimally adequate treatment among patients with depressive disorders.

It is however important to highlight that in both the US & Finland studies, the criteria for “minimally adequate treatment” included, in addition to the prescription of the appropriate pharmacotherapy, at least 4 visits with the physician over a 12-month period, with at least 8 sessions of psychotherapy for the patients with depression in Finland. In our study, only adequacy of the pharmacotherapy prescribed by the GP was assessed and it was actually higher for patients with several visits, than for patients with only one visit. Medicines selected as first-line treatment were consistent with their approved indications and international recommendations, for most patients. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the study planned to assess, with a psychiatrist, the accuracy of diagnoses made by GPs and the quality of care provided to patients could not take place.

Another limitation of our program is the fact that out of the top three barriers to treatment mentioned in the baseline survey, our intervention failed to address the first one, the cost of medications.

Digital technology was particularly useful in ensuring that people who were suspected of having a mental disorder by CHWs, would actually see a GP, and in facilitating the collection and sharing of information between CHWs and GPs. When we asked GPs during the program, to what extent the digital tools (tablet & app) was helpful, 43·9% of them selected “to a great extent”, 53·7% “to some extent”, 2·4% “not really” and 0% “not at all”. However additional training was required by some users, and there were also connectivity issues, which both would need to be taken into account for future use.

Two groups of CHWs (out of the five involved in total) were responsible for more than half (58·3%) of the people identified as suspected cases (Appendix 10, figure S.1). Our analysis showed that overall, CHWs’ average KAP score increased after training, however we could not see a relationship between CHWs’ end-line KAP score and the number of screened patients or the level of agreement with GPs’ diagnoses (Appendix 10, figures S.4, S.5). Another limitation is that data regarding the socio-demographic profile of GPs and CHWs were not collected as part of this project. Factors that influence CHWs’ productivity would be important to identify to improve efficiency and strengthen future programs: integration of CHWs within their community, how long they have lived in the township, the roles they have played etc. as well as the supervision provided by their coordinators might be important factors to consider.

The intervention resulted in 1,088 people being diagnosed with a mental disorder or epilepsy, and treated for it, out of the estimated 9,444 with depression, psychosis or epilepsy not treated in the township (based on the prevalence rates, treatment gap from the baseline survey – Appendix 2, table S.1 – and the total township population of 515,570). This would represent an 11·5% reduction. However, another limitation of our work is that we didn’t collect information about compliance with treatment, therefore this could be misleading to refer to this reduction as a “reduction in treatment gap”.

This program is one of the few studies regarding the effects of a mental health community intervention in Myanmar. However, during the 2-year implementation phase, only 1,378 cases were identified by CHWs, which remained small relative to the total population in the township, and among the 1,186 patients who saw a GP, only 938 had more than one visit recorded. Nevertheless, concordance between CHWs’ screenings and GPs’ diagnoses was high, highlighting CHWs’ ability to identify patients with mental disorders and epilepsy. The lowest concordance was for “undetermined” (12·7%) (Appendix 5; Table S.4) with CHWs identifying that there was a mental health issue with the patient but not necessarily which one, whereas the GP was able to diagnose the specific disorder.

Our study showed an increase in KAP scores for all 3 groups: CHWs, GPs and general population. However, some loss to follow-up for both GPs and CHWs regarding post-training and post-intervention KAP surveys, as well as differences between the baseline and end-line community samples are additional limitations. The main reasons for CHWs to leave the project were dismissal for lack of performance, or resignation to work on another project

,

,

our study suggests that developing skills and competencies of frontline health workers led to patients with mental disorders being identified, diagnosed and managed, and that raising awareness in the township might have helped change attitudes and practices within the community.

Door-to-door survey and interviews can be time-consuming as researchers will have to visit individual households to meet the respondents, and sit with them for some time. Sometimes respondents were not available during daytime and we lost a number of participants at the time of survey. Furthermore, reliability results were present but a confirmatory factor analysis (inter-rater and intra-rater validity) was not conducted in the validation part.

Additional limitations include the fact that there was no comparison with a non-intervention/control group and that there was limited involvement of service users in the evaluation of our programme. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the various lockdowns, some of the surveys were delayed and others could not take place such as the work planned to survey patients who had been referred by CHWs and had seen GPs, and similarly for the evaluation of the effectiveness of the low-cost digital technology used in Myanmar. These would require future work.