In the 1990s, the vast, empty halls of Helsinki’s Cable Factory began to echo to the sounds of electronic music, the heavy digital beats replacing the one-time thrum of heavy machinery. Thirty years on from those illegal raves and the occupation of the empty industrial complex by artists, DJs, dancers and designers, music and movement have been institutionalised with the opening of the Dance House Helsinki.

The building is referred to by architect Teemu Kurkela of JKMM as a “machine for dance”, an attempt to tie the place back to its industrial history as a facility for the manufacturing of cables. The factory, built in the early 1940s, spanned the maritime industry, punitive postwar reparations to the USSR and the early years of Finnish success story Nokia in its previous incarnation as a maker of cables. It is a perfect example of the shift from industrial to cultural production.

Those taut lengths of twisted steel have been replaced by a different kind of sinew: those of the bodies that the new space has been built for. The Dance House is a mix of chunky industrial archaeology and a robust new metal box expressed on the outside with a skin of steel and an op-art chainmail of metallic discs.

The interior is so stripped of detail and boxy in form that it can seem as if the architecture was omitted. Steel panels, concrete stairs, concrete floors, bleacher seating and ceilings of endless industrial steel grids remake it as a conspicuously industrial spectacle. It is a deliberate ploy to deflect the eye from the structure to the performers on stage or mingling pre- or post-performance. The design bows down before the event.

The first space encountered is an old courtyard, now roofed over in steel and glass, the old factory walls to either side. It has become a kind of covered street with, to one side, the museums and showrooms of the existing complex and, to the other, the new Dance House.

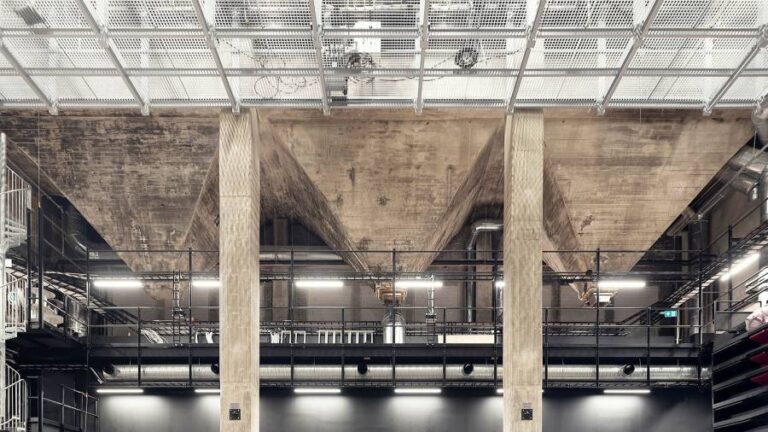

Passing through a set of heavy doors the visitor is deposited in a steel-lined black box, a raw, unadorned space. The first new performance space is set into one side of a former machine hall, the concrete hoppers looming up like inverted pyramids and the gantries for lighting looking as industrial as anything that might have been here before.

With the ducts and cables snaking up the walls, spiral steel stairs and strip-lighting, the ensemble resembles the kind of Constructivist fantasias the Russians indulged in during the 1920s. It’s an effect amplified behind the seating, where a tangle of steel struts and poles creates a dark metal forest as much out of a Finnish fairytale as its factory past. It looks like a space desperate to find a function.

The main hall is an entirely new space, a great black cube with a wall that can be lowered to conjoin it with the smaller hall. With a capacity of 700, it has a wraparound stage apparently as large as the auditorium, with the effect that the audience almost seems to be on the stage. This is performance as production, a robust container for an explosion of movement that does not distract from it in any way.

There is one more space downstairs, a reminder of what was once Finland’s biggest building and of the uncertainties in the time of its construction. A sprawling bomb shelter in the basement, chunky concrete columns marching through the low-ceilinged space, displays memories of the raves and parties held here during freezing Finnish winters once the factories above had been abandoned. Graffiti tags have been left on the doors and the concrete along with remnants of the old controls, dials, signs and thermometers.

The heavy concrete slabs have been cut through in the way Gordon Matta-Clark used to perforate derelict industrial buildings in New York to expose underlying structure and comment on the disposability of buildings rich in layers of history. Here, too, the scars of successive incarnations have been left clear to see.

The new concrete work aims to emulate the 1940s original and ends up resembling the kind of Brutalist volumes familiar from London’s South Bank, the direct line between the functional and the cultural drawn through an architecture of intense density. The new steelwork is simple and considered, so subtle that you barely notice it.

Outside that intensity is lost a little. Even with a huge facade of steel and those Paco Rabanne-type discs, the more self-conscious exterior lacks the industrial power of the spaces inside. The intention, Teemu tells me, was to allude to the body of a dancer in which grace and flow conceal huge strength and effort. It’s a nice metaphor, but there is plenty here in this massive structure to hold the attention, and it hardly needs another signpost. The landscape around it is still evolving but inside, at least, this is a series of spaces as full of power and potential as you could hope for.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture critic

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first