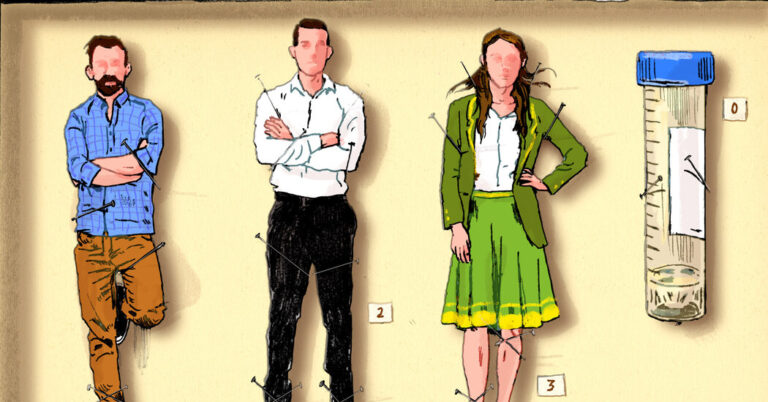

Korelitz’s plot points are in some ways old-fashioned — a tragic accident, an extramarital affair, a secret bequest, a mysterious letter — and in some ways new: “therapy goals,” cancel culture. The struggles here are classic — sibling rivalry, infidelity — and also contemporary. Conceived in a lab, the Oppenheimer triplets maintain a chill, asserting their individuality in ways both creative and cruel. As a child, Sally throws away Harrison’s chess medal. As Cornell students in adjacent dorms, Lewyn and Sally pretend they don’t have a sibling on campus. What a blessing for these three and for the reader that Phoebe, frozen at the same time but born almost 19 years later, grows up with the perspective to decode and partially disarm her tragicomic family.

At times this book suffers from an embarrassment of riches. The plot is ingenious, the pacing brisk — but the reader longs to delve deeper. Joanna fades into the background as her children grow. Her pain is palpable, but her main trait is denial. “Their mother, as long as Lewyn could remember, had hoarded and imbued with great significance such tiny moments, all while seeing so little of who the three of them actually were.” As Joanna clings to the illusion of family unity, she begins to “slide away,” and the reader loses her point of view as well. We see the consequences of her actions in the second half of the novel, but we can no longer access the mixture of pain and idealism motivating them.

Salo’s response to art provides some of the best passages in the book. Encountering a painting by Cy Twombly, he faints, overcome by “that orange, that red, those rhythmic loops, their valiant attempt to scribble something away.” Here we glimpse something of the banker’s soul as he responds to color and dynamic form, but the novel moves on quickly. Events overtake emotion, and we are left to view Salo as his wife and children do, as a cipher. His “attentive self, his essential self” slips offstage and off the page.

Self-aware and self-deprecating, Phoebe is an engaging young woman, summing up her own situation: “Privilege and tragedy. The perfect storm for any adolescent.” But her utility is such that in the final chapters of this complex book, she becomes a Swiss Army knife of a character — interventionist (“I want to talk about some things”), girl detective (“So would you please tell me about the legal troubles?”), pardoner (“You didn’t know it was the last thing you’d ever say to him”) and matchmaker (“Maybe it’s something the two of you should talk about”).

As for the triplets, “in full flight from one another as far back as their ancestral petri dish” — their loathing becomes limiting. A more nuanced relationship would raise the stakes on the fateful night when the siblings turn on one another. In the event, their entrenched antipathy undercuts the drama of mutual betrayal.