Small actions, at scale, can make a big difference, says Pamela Coke-Hamilton, executive director, International Trade Centre (ITC). This proverb holds true as we collectively confront what the United Nations Secretary-General has called “the defining issue of our time”: climate change.

Here is a staggering statistic: Half of the world population is “highly vulnerable” to the effects of climate change, with people in those regions 15 times more likely to die due to floods, droughts and storms compared to those in less vulnerable regions.

Many of the most vulnerable countries, which did the least to get us in this situation, are hardest hit by its effects. African countries, for example, account for 3% of global emissions, yet the continent is home to at least half of the most vulnerable countries. And they don’t have the time or resources to act.

For developing countries, it’s been one wave after another: First Covid-19, then the conflict in Ukraine and cost-of-living increases, on top of growing climate-related threats.

But here’s the good news: It’s not too late to make a change. And the change starts small.

Engaging the “silent majority”

If we are to take on this existential crisis, we as the global community have to do something we haven’t yet done: Fully engage the “silent majority”, or small businesses, in particular those in developing countries, so they can make the low-carbon transition.

Small firms make up 90% of companies and half of jobs worldwide. Of the big corporations that produce most of the goods we use every day – including food, electronics and apparel –more than 80% of their emissions come from their supply chains, and the biggest bulk of that comes from small businesses.

So small businesses have a major role to play in the low-carbon transition, both as contributors and beneficiaries. Their collective action in adapting to and mitigating climate change is key to curbing global temperature rise to 1.5°C – and if that target is slipping out of reach, as close to it as possible – as countries agreed to do in the Paris Agreement. Right now, we are not on course to meet that target.

Countries’ current plans to lower emissions, also known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), would lead to an 11% increase in emissions by 2030.

Drastic changes in behaviour are required, and small businesses in developing countries are aware and willing to make a change. The International Trade Centre (ITC) found that nearly 70% of small firms in sub-Saharan Africa see environmental risks as significant for business. The problem is, less than 40% can do something about it, versus 60% of large firms.

Simply put, small businesses in developing countries lack the skills, technology and finance to make the transition.

For those who can skill up and scale up, the door would open to lucrative business opportunities. Emerging due diligence and deforestation requirements in the European Union, for example, are putting the pressure on big corporations to source from “green” suppliers who can provide evidence of reducing emissions. There is a first-mover advantage for those who act now.

Mitigating, adapting, financing – the greatest of these?

Getting on track to meet the 1.5°C target hinges on making progress in three areas – mitigation, adaptation, financing – the last of which makes the first two possible.

On financing, African countries need $277 billion per year between 2020-2030 to implement their NDCs. That requires scaling up annual mitigation finance by 13 times, and annual adaptation finance by 6 times.

So the yearly financing required by Africa alone is nearly three times the $100bn yearly commitment of developed countries to support all developing countries – of which only seven countries mobilised their fair share in 2020. On top of this financing required by developing countries for mitigation and adaptation, an additional $400 billion a year is needed to cover loss and damage.

Those are a lot of numbers. All those figures can be summarized in this sentence: The asks may sound high, but the costs of not acting are even higher.

The nature of financing also matters. More needs to come through as grants or investments, especially at the country level. In 2019-2020, the bulk of climate financing was raised as debt. Developing countries already reeling from multiple crises will not be able to get their footing by taking on more debt.

Whatever the financing gap at the country level, the cracks are magnified at the small business level. What they need most are short-term, low-risk loans, according to ITC surveys of thousands of firms.

Since 2019, ITC has facilitated more than $68m in financing and investment for small businesses in more than 60 countries. Of that amount, nearly three-quarters – $50m – was purely green financing. The focus is on making financing not only available, but accessible.

To secure funding for small firms, some funds from donor and development finance institutions are used to de-risk guarantees for financing providers. Guarantors and financing providers agree to accept slightly lower returns in exchange for higher volumes of lending. Diversification of default risk across hundreds of small businesses – trained by ITC – helps make investing in them more attractive.

ITC as the joint agency of the United Nations and World Trade Organization, focusing on supporting small businesses to export, works closely with financing providers, guarantors, business development experts, governments and small businesses to equip small firms with the skills, tech and access to financing they need to compete in international markets – including in emerging green markets.

For example, ITC is working with G7 country organisations to help small businesses to comply with green corridor (sustainable transport routes) and digital environmental, social and governance (ESG) passport requirements of the European Union, which will come into force in 2023. Small businesses looking for new opportunities in the European market will have to adapt by switching to greener packaging or using more environmentally friendly agricultural practices, among other actions.

Ensuring a just transition

Equipping small businesses in developing countries to make the low-carbon transition is key, to ensure no one gets left behind. The green transition must be a just transition.

So as countries urgently work to mitigate and adapt to climate change, in line with their NDCs (as well as updating their NDCs to keep the 1.5°C goal in view), it cannot come at the cost of Africa’s development.

The reality is, as demand for fossil fuels declines with the move to renewable energy sources, Africa risks being left with stranded carbon assets. More than 185 countries agreed in Paris to leave two-thirds of fossil fuels in the ground. The problem is that many African countries are dependent on natural resources, including fossil fuels and minerals.

Africa needs a long-term strategy on the future of fossil fuels and the shift to greener energy sources. It should cover ways that even small businesses can pivot to renewable or resource-efficient energy options. Research shows that 90% of people live in places where using renewable energy would be cheaper than using fossil fuels. Solar power may even become “the cheapest source of electricity in history”.

A key strategy to mitigate the effects of climate change, without slowing the pace of Africa’s development, is to invest in regional trade – as part of the African Continental Free Trade Area – and adding value to goods, within the continent. This move would boost intra-African trade while reducing transport-related emissions. Transport as a sector is one of the world’s biggest emitters, equal to what the entire continent of Africa emits.

Making decisions based on data

Ideas are easy, adaptation is harder. Changes in policy, technology and markets require sound decision-making, to make it easier for businesses to adapt.

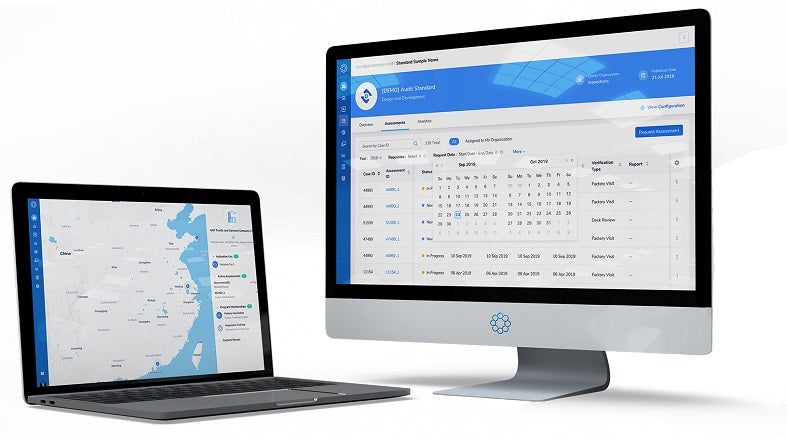

In support of these efforts, ITC launched two online tools at COP27: a data-backed tool to help policymakers and investors make decisions based on a comprehensive analysis of the risks and opportunities along agricultural value chains, and the Climate Smart Network to connect buyers with green suppliers in developing countries. ITC also launched a report outlining a ten-step plan to building the climate resilience of small businesses across value chains.

With COP27 now at a close, what is clear is that none of us can tackle the greatest challenge of our time alone. But working together – government, business, institutions and development partners – we can empower the voiceless, make visible the silent, and work towards a just transition that leaves no one behind.